Nicodemus, a rich and powerful jew, had many questions for Jesus, but came late at night to see Him out of fear of the jewish Establishment

“The Fire of Rome,” 1861, by Karl von Piloty (1826-66, the greatest German realistic painter of the 19th century.) According to Tacitus, Nero targeted [ = scapegoated] Christians as those responsible for the fire.

This brilliant book in French, which needs to be translated into English, German, Russian, Spanish, etc.,

…details the vicious slanders the jews cooked up to get both mobs and Roman authorities to massacre Christians. Christians, the jews said, were cannibals, practiced incest, and hated the human race. (Talk about accusatory inversion!)

And every time a drought, famine, plague, hurricane or earthquake struck an area, the jews would rile up a mob, saying “The Christians disrespect your gods, and have enraged them! Kill them to end the wrath of your gods!”

“Jewish Antichristianism” author Martin Peltier also suggests that the jews gave Nero the idea of blamng the Christian for the horrendous fire, which had destroyed 500-year-old temples and other famous and historical places. They worked on Nero’s wife Poppaea, who was favorable to jewry.

The Jewish historian Josephus paints a picture of Poppaea as “a worshipper of the God of Israel” and writes that she urged Nero to show compassion to the Jewish people. Did she also tell him to “get” the Christians?

This whole slanderous and cruel campaign was yet another amazing jewish disinformation achievement, since the Christians actually were sexually prim and proper, paid their taxes, told wives to respect and obey their husbands, were opposed to any revolt against Rome, served in the legions defending Rome, and avoided violence, theft, drunkenness, adultery, murder, etc.

In fact, Christianity attracted people bothered by a guilty conscience who both felt sorrow for hurting others and also feared divine wrath — in this life or after death — for the wrongs they had committed. Romans believed in both heaven — Elysium — and in Hell, Tartarus.

The original salvation teaching of Jesus (NOT of Saul/Paul) was to sincerely repent of your sins, show true remorse to your victim, apologize, make restitution in some way if possible, etc.

(Saul taught almost none of Jesus teachings, and hardly ever quoted from the man. His doctrine was that Jesus had died as a kind of human animal sacrifice, and that God could not forgive us our sins unless we see in the execution of Jesus not an outrageous frame-up by the jews of an innocent and godly man but a sacrifice, just as in the jewish Temple in Jerusalem, where rabbits or sheep had their throats slit to calm down an enraged Yahweh. This notion was by far the jewiest and most Old-Testamenty thing that Saul ever smuggled into Christianity, the crucifixion as a sacrifice to appease an enraged deity.)

Jesus taught us, however, to apologize to God for having harmed one of HIS human creatures, and to ask “Our Father in Heaven” for mercy. Jesus said that God (not Yahweh) is a loving heavenly father who forgives His children with joy if they truly repent. In teaching this salvation through repentance, Jesus taught this parable: In the Parable of the Prodigal Son, the father represents God and teaches us some valuable lessons concerning parenting. Christian fathers need to imitate the example of the father in this parable.

The father is patient: The boy had been gone a long time, long enough for a famine to ravish the land, yet the father waited patiently. Indeed patience is a virtue all Christians should possess (Galatians 5:22). But oh how necessary it is in our homes! We need to learn to be patient with our children, knowing that they have much to learn. We must realize that they are not miniature adults. There is much to learn, and some lessons must be learned the hard way. We cannot learn the lessons for them, nor can we teach them. The prodigal son had to learn some hard lessons, and the father allowed it. Likewise we must learn patience. Fathers, how patient are you with your children as they falter along life’s path?

The father is loving: When he saw the boy coming, while he was still a long way off, the father ran to him and hugged and kissed him. He doesn’t ask him where he had been or what he had been doing.

There is no lecture saying, “I told you so” or “You should have known better.” There is no “I hope you’ve learned your lesson” speech. There is simply the love of a father and the joy that his son has returned. We don’t know what the boy may have expected, perhaps he delayed his return because he was too ashamed to face his father. But the love of his father removed his fear. “And above all things have fervent love for one another, for ‘love will cover a multitude of sins,’” (1 Peter 4:8). Fathers, how loving are you when your children make mistakes?

The father is forgiving: His actions demonstrated it. The boy was ready to ask to be made like one of his fathers hired servants, yet his father did not let him finish his plea. Once the son had repented he was restored to his original place. Not only that, but they have a party to celebrate his return! We need to learn to be forgiving of those who have done wrong. We should focus not on the wrong they have done but on the joy that they have repented. So much sorrow could be avoided if we will simply learn to do this. “And be kind to one another, tender-hearted, forgiving one another, even as God in Christ forgave you,” (Ephesians 4:32). Fathers, how forgiving are you of your children when they do wrong?

The father has his priorities in the right place: The most important thing was not that his son had sinned, nor that he had wasted his inheritance. Neither was it important that he’d caused his father untold grief. The most important thing was that his son was home. Material things can be replaced, sorrows can be forgotten, and sin can be forgiven, but a soul lost can never be restored. We need to keep in mind the inherent value of the soul. “For what will it profit a man if he gains the whole world and loses his own soul? Or what will a man give in exchange for his soul?” (Mark 8:36,37). Fathers, where are your priorities?

….”The Romans cooked up Gentle Jesus to make the Jews peaceful”

“Jesus, was in fact, Titus,” I was told. Hunh? This Roman general and emperor who flourished 30 years after Jesus WAS Jesus?

This Jesus-was-invented-by-Rome theory is being pushed by the (IMO closet Jew) Joseph Atwill.

As this book in French proves, the Jews have financed Jesus-debunking and Jesus-mocking, and defamed Christians and agitated for them to be murdered, for nearly two thousand years straight now.

And also they have backed Protestantism as a Catholicism-debunker. … and the Scofield Bible as an Israel-booster.

Brant Pitre’s outstanding book debunks thoroughly the notion that the fiercely anti-Pharisee Jesus never existed, or that He was a lunatic or a liar.

Crypto-khazar Atwil engages in goy-mocking with his slander that Jesus never existed. He informs us that the Roman state was the inventor of this non-existent Jesus; that it totally “cooked Him up” to give the Jews a peaceful messiah, a Prince of Peace, instead of a warlike one, a messiah who had already come and gone, you see, and whose “kingdom is not of this world.”

Sooooo if the Jews accepted this, then they would be induced to stop revolting and trying to expel the Romans from Palestine, and also cut out the massacring of Gentiles elsewhere. “Love thy enemies,” “turn the other cheek,” the Gentiles are okay,” and “God is love.”

In reality, the Jews stayed as aggressive and horrific as ever and so the supposedly Roman invention of Christianity had zero effect on them and their values of hate, enslavement, rape, torture and death.

The half-truth is that Jesus WAS indeed on a mission to defang the incredibly dangerous Jews.

I would ask any Atwillians: Do you realize how much the Jews HATE Jesus, and why? Do you realize you are denying the very existence of an innocent man whom the Jews had hideously tortured and murdered?

Do you understand you are deriding and disrespecting the white men and women who, at the instigation of Jews (from the time of Nero and his Jew-loving wife Poppaea on), were eaten by lions and burned alive?

Do you grasp that Jesus was racially and spiritually an Aryan?

What I have noticed over the years is that so very many atheists and heathens are full of ego and hatred.

I state here and now that whatever “heathens” think, humility IS a great virtue. To be free of ego, arrogance and selfishness, and serve others, IS a wonderful thing.

Jesus washed the feet of his own disciples to teach them to stop boasting who was his top follower.

“And He took with Him Peter and the two sons of Zebedee, and began to be grieved and distressed. Then He said to them, “My soul is deeply grieved, to the point of death; remain here and keep watch with Me.” And He went a little beyond them, and fell on His face and prayed, saying, “My Father, if it is possible, let this cup pass from Me; yet not as I will, but as You will.” — Jesus, Matthew 26:37-39

To be open to new ideas and to accept correction is a great blessing.

And this is why Jesus, like the Buddha before him, had a very important message.

“Ego Causes Suffering.” — Buddha

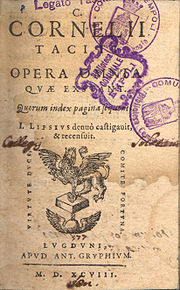

The Roman historian and senator Tacitus referred to Jesus, his execution by Pontius Pilate, and the existence of early Christians in Rome in his final work, Annals (written c. AD 116), book 15, chapter 44.[1]

The context of the passage is the six-day Great Fire of Rome that burned much of the city in AD 64 during the reign of Roman Emperor Nero.[2] The passage is one of the earliest non-Christian references to the origins of Christianity[broken anchor], the execution of Christ described in the canonical gospels, and the presence and persecution of Christians in 1st-century Rome.[3][4]

There are two points of vocabulary in the passage. First, Tacitus may have used the word “Chrestians” (Chrestianos) for Christians, but then speaks of “Christ” (Christus) as the origin of that name. Second, he calls Pilate a “procurator”, even though other sources indicate that he had the title “prefect”. Scholars have proposed various hypotheses to explain these peculiarities.

The scholarly consensus is that Tacitus’s reference to the execution of Jesus by Pontius Pilate is both authentic, and of historical value as an independent Roman source.[5][6][7] However, Tacitus does not reveal the source of his information. There are several hypotheses as to what sources he may have used.

Tacitus provides non-Christian confirmation of the crucifixion of Jesus.[8][9] Scholars view it as establishing three separate facts about Rome around AD 60: (i) that there was a sizable number of Christians in Rome at the time, (ii) that it was possible to distinguish between Christians and Jews in Rome, and (iii) that at the time pagans made a connection between Christianity in Rome and its origin in Roman Judaea.[10][11]

Tacitus is one of the non-Christian writers of the time who mentioned Jesus and early Christianity along with Flavius Josephus, Pliny the Younger, and Suetonius.[12]

The passage and its context

[edit]

The Annals passage (15.44), which has been subjected to much scholarly analysis, follows a description of the six-day Great Fire of Rome that burned much of Rome in July 64 AD.[13] The key part of the passage reads as follows (translation from Latin by A. J. Church and W. J. Brodribb, 1876):

|

Sed non ope humana, non largitionibus principis aut deum placamentis decedebat infamia, quin iussum incendium crederetur. Ergo abolendo rumori Nero subdidit reos et quaesitissimis poenis adfecit, quos per flagitia invisos vulgus Chrestianos appellabat. Auctor nominis eius Christus Tibero imperitante per procuratorem Pontium Pilatum supplicio adfectus erat; repressaque in praesens exitiabilis superstitio rursum erumpebat, non modo per Iudaeam, originem eius mali, sed per Urbem etiam, quo cuncta undique atrocia aut pudenda confluunt celebranturque. igitur primum correpti qui fatebantur, deinde indicio eorum multitudo ingens haud proinde in crimine incendii quam odio humani generis convicti sunt.[14] |

But all human efforts, all the lavish gifts of the emperor, and the propitiations of the gods, did not banish the sinister belief that the conflagration was the result of an order. Consequently, to get rid of the report, Nero fastened the guilt and inflicted the most exquisite tortures on a class hated for their abominations, called Christians by the populace. Christus, from whom the name had its origin, suffered the extreme penalty during the reign of Tiberius at the hands of one of our procurators, Pontius Pilatus, and a most mischievous superstition, thus checked for the moment, again broke out not only in Judæa, the first source of the evil, but even in Rome, where all things hideous and shameful from every part of the world find their centre and become popular. Accordingly, an arrest was first made of all who pleaded guilty; then, upon their information, an immense multitude was convicted, not so much of the crime of firing the city, as of hatred against mankind. |

Tacitus then describes the torture of Christians:

Mockery of every sort was added to their deaths. Covered with the skins of beasts, they were torn by dogs and perished, or were nailed to crosses, or were doomed to the flames and burnt, to serve as a nightly illumination, when daylight had expired. Nero offered his gardens for the spectacle, and was exhibiting a show in the circus, while he mingled with the people in the dress of a charioteer or stood aloft on a car.

Hence, even for criminals who deserved extreme and exemplary punishment, there arose a feeling of compassion; for it was not, as it seemed, for the public good, but to glut one man’s cruelty, that they were being destroyed.[15]

The exact cause of the fire remains uncertain, but much of the population of Rome suspected that Emperor Nero had started the fire himself.[13] To divert attention from himself, Nero accused the Christians of starting the fire and persecuted them, making this the first documented confrontation between Christians and the authorities in Rome.[13] Tacitus suggested that Nero used the Christians as scapegoats.[16]

As with almost all ancient Greek and Latin literature,[17] no original manuscripts of the Annals exist. The surviving copies of Tacitus’ major works derive from two principal manuscripts, known as the Medicean manuscripts, which are held in the Laurentian Library in Florence, Italy.[18] The second of them (Plut. 68.2), as the only one containing books xi–xvi of the Annales, is the oldest witness to the passage describing Christians.[19] Scholars generally agree that this codex was written in the 11th century at the Benedictine abbey of Monte Cassino and its end refers to Abbas Raynaldus cu… who was most probably one of the two abbots of that name at the abbey during that period.[19]

Points of vocabulary

[edit]

Christians and Chrestians

[edit]

The passage states:

… called Christians by the populace. Christus, from whom the name had its origin …

In 1902 Georg Andresen commented on the appearance of the first ‘i’ and subsequent gap in the earliest extant, 11th century, copy of the Annals in Florence, suggesting that the text had been altered, and an ‘e’ had originally been in the text, rather than this ‘i’.[20] “With ultra-violet examination of the MS the alteration was conclusively shown. It is impossible today to say who altered the letter e into an i.”[21] Since the alteration became known it has given rise to debates among scholars as to whether Tacitus deliberately used the term “Chrestians”, or if a scribe made an error during the Middle Ages.[22][23] It has been stated that both the terms Christians and Chrestians had at times been used by the general population in Rome to refer to early Christians.[24] Robert E. Van Voorst states that many sources indicate that the term Chrestians was also used among the early followers of Jesus by the second century.[23][25] The term Christians appears only three times in the New Testament, the first usage (Acts 11:26) giving the origin of the term.[23] In all three cases the uncorrected Codex Sinaiticus in Greek reads Chrestianoi.[23][25] In Phrygia a number of funerary stone inscriptions use the term Chrestians, with one stone inscription using both terms together, reading: “Chrestians for Christians“.[25]

Adolf von Harnack argued that Chrestians was the original wording, and that Tacitus deliberately used Christus immediately after it to show his own superior knowledge compared to the population at large.[23] Robert Renehan has stated that it was natural for a Roman to mix the two words that sounded the same, that Chrestianos was the original word in the Annals and not an error by a scribe.[26][27] Van Voorst has stated that it was unlikely for Tacitus himself to refer to Christians as Chrestianos i.e. “useful ones” given that he also referred to them as “hated for their shameful acts”.[22] Eddy and Boyd see no major impact on the authenticity of the passage or its meaning regardless of the use of either term by Tacitus.[28]

Whatever the original wording of Tacitus, another ancient source about the Neronian persecution, by Suetonius, apparently speaks of “Christians”: “In Suetonius’ Nero 16.2, ‘christiani‘, however, seems to be the original reading.”[21]

The rank of Pilate

[edit]

Pilate’s rank while he was governor of Judaea appeared in a Latin inscription on the Pilate Stone which called him a prefect, while this Tacitean passage calls him a procurator. Josephus refers to Pilate with the generic Greek term ἡγεμών (hēgemṓn), or governor. Tacitus records that Claudius was the ruler who gave procurators governing power.[29][30] After Herod Agrippa‘s death in AD 44, when Judea reverted to direct Roman rule, Claudius gave procurators control over Judea.[13][31][32][33]

Various theories have been put forward to explain why Tacitus should use the term “procurator” when the archaeological evidence indicates that Pilate was a prefect. Jerry Vardaman theorizes that Pilate’s title was changed during his stay in Judea and that the Pilate Stone dates from the early years of his administration.[34] Baruch Lifshitz postulates that the inscription would originally have mentioned the title of “procurator” along with “prefect”.[35] L.A. Yelnitsky argues that the use of “procurator” in Annals 15.44.3 is a Christian interpolation.[36] S.G.F. Brandon suggests that there is no real difference between the two ranks.[37] John Dominic Crossan states that Tacitus “retrojected” the title procurator which was in use at the time of Claudius back onto Pilate who was called prefect in his own time.[38] Bruce Chilton and Craig Evans as well as Van Voorst state that Tacitus apparently used the title procurator because it was more common at the time of his writing and that this variation in the use of the title should not be taken as evidence to doubt the correctness of the information Tacitus provides.[39][40] Warren Carter states that, as the term “prefect” has a military connotation, while “procurator” is civilian, the use of either term may be appropriate for governors who have a range of military, administrative and fiscal responsibilities.[41]

Louis Feldman says that Philo (who died AD 50) and Josephus also use the term “procurator” for Pilate.[42] As both Philo and Josephus wrote in Greek, neither of them actually used the term “procurator”, but the Greek word ἐπίτροπος (epítropos), which is regularly translated as “procurator”. Philo also uses this Greek term for the governors of Egypt (a prefect), of Asia (a proconsul) and Syria (a legate).[43] Werner Eck, in his list of terms for governors of Judea found in the works of Josephus, shows that, while in the early work, The Jewish War, Josephus uses epitropos less consistently, the first governor to be referred to by the term in Antiquities of the Jews was Cuspius Fadus, (who was in office AD 44–46).[44] Feldman notes that Philo, Josephus and Tacitus may have anachronistically confused the timing of the titles—prefect later changing to procurator.[42] Feldman also notes that the use of the titles may not have been rigid, for Josephus refers to Cuspius Fadus both as “prefect” and “procurator”.[42]

Authenticity

[edit]

Most scholars hold the passage to be authentic and that Tacitus was the author.[45][46][47]

Classicists observe that in a recent assessment by latinists on the passage, they unanimously deemed the passage authentic and noted that no serious Tacitean scholar believes it to be an interpolation.[48]

Suggestions that the passage may have been a complete forgery have been generally rejected by scholars.[49][50] John P. Meier states that there is no historical or archaeological evidence to support the argument that a scribe may have introduced the passage into the text.[51] Scholars such as Bruce Chilton, Craig Evans, Paul Eddy and Gregory Boyd agree with John Meier’s statement that “Despite some feeble attempts to show that this text is a Christian interpolation in Tacitus, the passage is obviously genuine”.[39][28]

Tacitus was a patriotic Roman senator.[52][53] His writings show no sympathy towards Christians, or knowledge of who their leader was.[5][54] His characterization of “Christian abominations” may have been based on the rumors in Rome that during the Eucharist rituals Christians ate the body and drank the blood of their God, interpreting the ritual as cannibalism.[54][55]Andreas Köstenberger states that the tone of the passage towards Christians is far too negative to have been authored by a Christian scribe.[56] Van Voorst also states that the passage is unlikely to be a Christian forgery because of the pejorative language used to describe Christianity.[57]

Tacitus was about seven years old at the time of the Great Fire of Rome, and like other Romans as he grew up he would have most likely heard about the fire that destroyed most of the city, and Nero’s accusations against Christians.[16] When Tacitus wrote his account, he was the governor of the province of Asia, and as a member of the inner circle in Rome he would have known of the official position with respect to the fire and the Christians.[16]

William L. Portier has stated that the references to Christ and Christians by Tacitus, Josephus and the letters to Emperor Trajan by Pliny the Younger are consistent, which reaffirms the validity of all three accounts.[58]

Sources used by Tacitus

[edit]

The majority of scholars consider the passage to be genuinely by Tacitus. However, he does not reveal the source of his information. For this reason, some scholars have debated the historical value of the passage.[59]

Gerd Theissen and Annette Merz argue that Tacitus at times had drawn on earlier historical works now lost to us, and he may have used official sources from a Roman archive in this case; however, if Tacitus had been copying from an official source, some scholars would expect him to have labelled Pilate correctly as a prefect rather than a procurator.[60] Theissen and Merz state that Tacitus gives us a description of widespread prejudices about Christianity and a few precise details about “Christus” and Christianity, the source of which remains unclear.[61] However, Paul Eddy has stated that given his position as a senator, Tacitus was also likely to have had access to official Roman documents of the time and did not need other sources.[28]

Scholars have also debated the issue of hearsay in the reference by Tacitus. Charles Guignebert argued that “So long as there is that possibility [that Tacitus is merely echoing what Christians themselves were saying], the passage remains quite worthless”.[62] R. T. France states that the Tacitus passage is at best just Tacitus repeating what he had heard through Christians.[63] However, Paul Eddy has stated that as Rome’s preeminent historian, Tacitus was generally known for checking his sources and was not in the habit of reporting gossip.[28]

Tacitus was a member of the Quindecimviri sacris faciundis, a council of priests whose duty it was to supervise foreign religious cults in Rome,which as Van Voorst points out, makes it reasonable to suppose that he would have acquired knowledge of Christian origins through his work with that body.[64]

Historical value

[edit]

Depending on the sources Tacitus used, the passage is potentially of historical value regarding Jesus, early Christianity, and its persecution under emperor Nero.

Regarding Jesus, Van Voorst states that “of all Roman writers, Tacitus gives us the most precise information about Christ”.[57] Crossan considers the passage important in establishing that Jesus existed and was crucified, and states: “That he was crucified is as sure as anything historical can ever be, since both Josephus and Tacitus… agree with the Christian accounts on at least that basic fact.”[65] Eddy and Boyd state that it is now “firmly established” that Tacitus provides a non-Christian confirmation of the crucifixion of Jesus.[9] Biblical scholar Bart D. Ehrman wrote: “Tacitus’s report confirms what we know from other sources, that Jesus was executed by order of the Roman governor of Judea, Pontius Pilate, sometime during Tiberius’s reign.”[66]

However, some scholars question the value of the passage given that Tacitus was born 25 years after Jesus’ death.[57]

Regarding early Christianity, scholars generally consider Tacitus’s reference to be of historical value as an independent Roman source that is in unison with other historical records.[5][6][7][58] James D. G. Dunn considers the passage as useful in establishing facts about early Christians, e.g. that there was a sizable number of Christians in Rome around AD 60.

Dunn states that Tacitus seems to be under the impression that Christians were some form of Judaism, although distinguished from them.[10] Raymond E. Brown and John P. Meier state that in addition to establishing that there was a large body of Christians in Rome, the Tacitus passage provides two other important pieces of historical information, namely that by around AD 60 it was possible to distinguish between Christians and Jews in Rome and that even pagans made a connection between Christianity in Rome and its origin in Judea.[11]

Regarding the Neronian persecution, the scholarly consensus is that it really took place.[67]

Questioning this consensus, Weaver notes that Tacitus spoke of the persecution of Christians, but no other Christian author wrote of this persecution for a hundred years.[68]

Brent Shaw has argued that Tacitus was relying on Christian and Jewish legendary sources that portrayed Nero as the Antichrist for the information that Nero persecuted Christians and that in fact, no persecution under Nero took place.[46]

Shaw has questioned if the passage represents “some modernizing or updating of the facts” to reflect the Christian world at the time the text was written.[69]

Shaw’s views have received strong criticism and have generally not been accepted by the scholarly consensus:[67] Christopher P. Jones (Harvard University) answered to Shaw and refuted his arguments, noting that the Tacitus’s anti-Christian stance makes it unlikely that he was using Christian sources; he also noted that the Epistle to the Romans of Paul the Apostle clearly points to the fact that there was indeed a clear and distinct Christian community in Rome in the 50s and that the persecution is also mentioned by Suetonius in The Twelve Caesars.[70] Larry Hurtado was also critical of Shaw’s argument, dismissing it as “vague and hazy”.[71]

Brigit van der Lans and Jan N. Bremmer also dismissed Shaw’s argument, noting that the Neronian persecution is recorded in many 1st-century Christian writings, such as the Epistle to the Hebrews, the Book of Revelation, the apocryphal Ascension of Isaiah, the First Epistle of Peter, the Gospel of John and the First Epistle of Clement; they also argued that Chrestianus, Christianus, and Χριστιανός were probably terms invented by the Romans in the 50s and then adopted by Christians themselves.[72]

John Granger Cook also rebuked Shaw’s thesis, arguing that Chrestianus, Christianus, and Χριστιανός are not creations of the second century and that Roman officials were probably aware of the Chrestiani in the 60s.[73]

Barry S. Strauss also rejects Shaw’s argument.[74]

Other early sources

[edit]

Tacitus is not the only non-Christian writer of the time who mentioned Jesus and early Christianity.

The earliest known references to Christianity are found in Antiquities of the Jews, a 20-volume work written by the Jewish historian Titus Flavius Josephus around 93–94 AD, during the reign of emperor Domitian. As it stands now, this work includes two references to Jesus and Christians (in Book 18, Chapter 3 and Book 20, Chapter 9), and also a reference to John the Baptist (in Book 18, Chapter 5).[75][76]

The next known reference to Christianity was written by Pliny the Younger, who was the Roman governor of Bithynia and Pontus during the reign of emperor Trajan. Around 111 AD,[77] Pliny wrote a letter to emperor Trajan. As it stands now, the letter is requesting guidance on how to deal with suspected Christians who appeared before him in trials he was holding at that time.[78][79][80] Tacitus’ references to Nero’s persecution of Christians in the Annals were written around 115 AD,[77] a few years after Pliny’s letter but also during the reign of emperor Trajan.

Another notable early author was Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus, who wrote the Lives of the Twelve Caesars around 122 AD,[77] during the reign of emperor Hadrian. In this work, Suetonius apparently described why Jewish Christians were expelled from Rome by emperor Claudius, and also the persecution of Christians by Nero, who was the heir and successor of Claudius.

See also

[edit]

Wikisource has original text related to this article:

- Annals (Tacitus)

- Tacitus

- Christianity in the 1st century

- Persecution of Christians in the Roman Empire

- Historicity of Jesus

- Sources for the historicity of Jesus

References

[edit]

- ^ P. E. Easterling, E. J. Kenney (general editors), The Cambridge History of Latin Literature, page 892 (Cambridge University Press, 1982, reprinted 1996).

- ^ Stephen Dando-Collins (2010). The Great Fire of Rome. ISBN978-0-306-81890-5. pp. 1–4.

- ^ Brent 2009, p. 32–34.

- ^ Van Voorst 2000, p. 39–53.

- ^ abc Evans 2001, p. 42.

- ^ ab Watson E. Mills, Roger Aubrey Bullard (2001). Mercer Dictionary of the Bible. ISBN0-86554-373-9. p. 343.

- ^ ab Helen K. Bond (2004). Pontius Pilate in History and Interpretation. ISBN0-521-61620-4. p. xi.

- ^ Mykytiuk, Lawrence (January 2015). “Did Jesus Exist? Searching for Evidence Beyond the Bible”. Biblical Archaeology Society.

- ^ ab Eddy & Boyd 2007, p. 127.

- ^ ab Dunn 2009, p. 56.

- ^ ab Brown, Raymond Edward; Meier, John P. (1983). Antioch and Rome: New Testament cradles of Catholic Christianity. Paulist Press. p. 99. ISBN0-8091-2532-3.

- ^ Van Voorst 2000.

- ^ abcd Brent 2009, p. 32-34.

- ^ “Tacitus: Annales XV”.

- ^ Tacitus, The Annals, book 15, chapter 44

- ^ abc Barnett 2002, p. 30.

- ^ L.D. Reynolds, N.G. Wilson, Scribes and Scholars. A Guide to the Transmission of Greek and Latin Literature, Oxford 1991

- ^ Cornelii Taciti Annalium, Libri V, VI, XI, XII: With Introduction and Notes by Henry Furneaux, H. Pitman 2010 ISBN1-108-01239-6 page iv

- ^ ab Newton, Francis, The Scriptorium and Library at Monte Cassino, 1058–1105, ISBN0-521-58395-0 Cambridge University Press, 1999. “The Date of the Medicean Tacitus (Flor. Laur. 68.2)”, p. 96-97.

- ^ Georg Andresen in Wochenschrift fur klassische Philologie 19, 1902, col. 780f

- ^ ab J. Boman, Inpulsore Cherestro? Suetonius’ Divus Claudius 25.4 in Sources and ManuscriptsArchived 2013-01-04 at archive.today, Liber Annuus 61 (2011), ISSN 0081-8933, Studium Biblicum Franciscanum, Jerusalem 2012, p. 355, n. 2.

- ^ ab Van Voorst 2000, p. 44-48.

- ^ abcde Bromiley 1995, p. 657.

- ^ Christians at Rome in the First Two Centuries by Peter Lampe 2006 ISBN0-8264-8102-7 page 12

- ^ abc Van Voorst 2000, p. 33-35.

- ^ Robert Renehan, “Christus or Chrestus in Tacitus?”, La Parola del Passato 122 (1968), pp. 368-370

- ^ Transactions and proceedings of the American Philological Association, Volume 29, JSTOR (Organization), 2007. p vii

- ^ abcd Eddy & Boyd 2007, p. 181.

- ^ Tacitus, Annals 12.60: Claudius said that the judgments of his procurators had the same efficacy as those judgments he made.

- ^ P. A. Brunt, Roman imperial themes, Oxford University Press, 1990, ISBN0-19-814476-8, ISBN978-0-19-814476-2. p.167.

- ^ Tacitus, Histories 5.9.8.

- ^ Bromiley 1995, p. 979.

- ^ Paul, apostle of the heart set free by F. F. Bruce (2000) ISBN1842270273 Eerdsmans page 354

- ^ “A New Inscription Which Mentions Pilate as ‘Prefect‘“, JBL 81/1 (1962), p. 71.

- ^ “Inscriptions latines de Cesaree (Caesarea Palaestinae)” in Latomus 22 (1963), pp. 783–4.

- ^ “The Caesarea Inscription of Pontius Pilate and Its Historical Significance” in Vestnik Drevnej Istorii 93 (1965), pp.142–6.

- ^ “Pontius Pilate in history and legend” in History Today 18 (1968), pp. 523—530

- ^ Crossan 1999, p. 9.

- ^ ab Chilton, Bruce; Evans, Craig A. (1998). Studying the historical Jesus: evaluations of the state of current research. pp. 465–466. ISBN90-04-11142-5.

- ^ Van Voorst 2000, p. 48.

- ^ Pontius Pilate: Portraits of a Roman Governor by Warren Carter (Sep 1, 2003) ISBN0814651135 page 44

- ^ abc Feldman 1997, p. 818.

- ^ Matthew and Empire: Initial Explorations by Warren Carter (T&T Clark: October 10, 2001) ISBN978-1563383427 p. 215.

- ^ Werner Eck, “Die Benennung von römischen Amtsträgern und politisch-militärisch-administrativenFunktionen bei Flavius Iosephus: Probleme der korrekten IdentifizierungAuthor” in Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik, 166 (2008), p. 222.

- ^ Van Voorst 2000, p. 42-43.

- ^ ab Shaw 2015.

- ^ Blom, Willem (2019), “Why the Testimonium Taciteum Is Authentic: A Response to Carrier”, Vigilae Christianae

- ^ Williams, Margaret H. (2023). Early Classical Authors on Jesus. T&T Clark. pp. 67–74. ISBN9780567683151.

- ^ Van Voorst 2000, p. 42.

- ^ Furneaux 1907, Appendix II, p. 418.

- ^ Meier, John P. (1991). A Marginal Jew: Rethinking the Historical Jesus. Vol. 1. Doubleday. pp. 168–171.

- ^ Feldman, Louis H. (1997). Josephus, the Bible, and history. p. 381. ISBN90-04-08931-4.

- ^ Powell, Mark Allan (1998). Jesus as a figure in history: how modern historians view the man from Galilee. Westminster John Knox Press. p. 33. ISBN0-664-25703-8.

- ^ ab Dunstan, William E. (2010). Ancient Rome. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 293. ISBN978-0-7425-6833-4.

- ^ Burkett, Delbert Royce (2002). An introduction to the New Testament and the origins of Christianity. Cambridge University Press. p. 485. ISBN0-521-00720-8.

- ^ Köstenberger, Andreas J.; Kellum, L. Scott (2009). The Cradle, the Cross, and the Crown: An Introduction to the New Testament. B&H Publishing. pp. 109–110. ISBN978-0-8054-4365-3.

- ^ abc Van Voorst 2000, p. 39-53.

- ^ ab Portier 1994, p. 263.

- ^ Bruce, F. F. (1974). Jesus and Christian Origins Outside the New Testament. Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. p. 23.

- ^ Theissen & Merz 1998, p. 83.

- ^ Theissen, Gerd; Merz, Annette (1998). The historical Jesus: a comprehensive guide. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. p. 83. ISBN978-0-8006-3122-2.

- ^ Jesus, University Books, New York, 1956, p.13

- ^ France, R. T. (1986). Evidence for Jesus (Jesus Library). Trafalgar Square Publishing. pp. 19–20. ISBN978-0-340-38172-4.

- ^ Van Voorst, Robert E. (2011). Handbook for the Study of the Historical Jesus. Leiden: Brill Publishers. p. 2159. ISBN978-9004163720.

- ^ Crossan, John Dominic (1995). Jesus: A Revolutionary Biography. HarperOne. p. 145. ISBN0-06-061662-8.

- ^ Ehrman, Bart D. (2001). Jesus: Apocalyptic Prophet of the New Millennium. Oxford University Press. p. 59. ISBN978-0195124743.

- ^ ab McKnight, Scot; Gupta, Nijay K. (2019-11-05). The State of New Testament Studies: A Survey of Recent Research. Baker Academic. ISBN978-1-4934-1980-7.

It appears to me that historians of ancient Rome generally accept Nero’s persecution of Christians

- ^ Weaver, Walter P. (July 1999). The Historical Jesus in the Twentieth Century: 1900–1950. A&C Black. pp. 53, 57. ISBN9781563382802.

- ^ Shaw, Brent (2015). “The Myth of Neronian Persecution”. Journal of Roman Studies. 105: 86. doi:10.1017/S0075435815000982. S2CID162564651.

- ^ Jones, Christopher P. (2017). “The Historicity of the Neronian Persecution: A Response to Brent Shaw”(PDF). New Testament Studies. 63: 146–152. doi:10.1017/S0028688516000308. S2CID164718138 – via Cambridge University Press.

- ^ “Nero and the Christians”. Larry Hurtado’s Blog. 2015-12-14. Retrieved 2021-09-14.

- ^ Van der Lans, Birgit; Bremmer, Jan N. (2017). “Tacitus and the Persecution of the Christians: An Invention of Tradition?”. Eirene: Studia Graeca et Latina. 53: 299–331 – via Centre for Classical Studies.

- ^ G. Cook, John (2020). “Chrestiani, Christiani, Χριστιανοί: a Second Century Anachronism?”. Vigiliae Christianae. 74 (3): 237–264. doi:10.1163/15700720-12341410. S2CID242371092 – via Brill.

- ^ Strauss, Barry (2020-03-03). Ten Caesars: Roman Emperors from Augustus to Constantine. Simon and Schuster. ISBN978-1-4516-6884-1.

- ^ Maier, Paul L. (1995). Josephus, the Essential Writings: A Condensation of Jewish Antiquities and the Jewish War. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Kregel Publications. p. 12. ISBN978-0825429637.

- ^ Baras, Zvi (1987). “The Testimonium Flavianum and the Martyrdom of James”. In Feldman, Louis H.; Hata, Gōhei (eds.). Josephus, Judaism and Christianity. Leiden: Brill Publishers. pp. 54–7. ISBN978-9004085541.

- ^ abc Crossan 1999, p. 3.

- ^ Carrington, Philip (1957). “The Wars of Trajan”. The Early Christian Church. Vol. 1: The First Christian Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 429. ISBN978-0521166416.

- ^ Benko, Stephen (1986). Pagan Rome and the Early Christians. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. pp. 5–7. ISBN978-0253203854.

- ^ Benko, Stephen (2014). “Pagan Criticism of Christianity during the First Centuries A.D.”. In Temporini, Hildegard; Haase, Wolfgang (eds.). Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen Welt. second series (Principat) (in German). Berlin: De Gruyter. pp. 1055–118. ISBN978-3110080162.

Works cited

[edit]

- Barnett, Paul (2002). Jesus & the Rise of Early Christianity: A History of New Testament Times. Downers Grove, Illinois: InterVarsity Press. ISBN978-0830826995.

- Brent, Allen (2009). A Political History of Early Christianity. Edinburgh: T&T Clark. ISBN978-0567031754.

- Bromiley, Geoffrey W. (1995). International Standard Bible Encyclopedia. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. ISBN978-0802837851.

- Crossan, John Dominic (1999). “Voices of the First Outsiders”. Birth of Christianity. Edinburgh: T&T Clark. ISBN978-0567086686.

- Dunn, James D. G. (2009). Beginning from Jerusalem (Christianity in the Making, vol. 2). Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. ISBN978-0802839329.

- Eddy, Paul R.; Boyd, Gregory A. (2007). The Jesus Legend: A Case for the Historical Reliability of the Synoptic Jesus Tradition. Ada, Michigan: Baker Academic. ISBN978-0801031144.

- Evans, Craig A. (2001). Jesus and His Contemporaries: Comparative Studies. Leiden: Brill Publishers. ISBN978-0391041189.

- Portier, William L. (1994). Tradition and Incarnation: Foundations of Christian Theology. Mahwah, New Jersey: Paulist Press. ISBN978-0809134670.

- Van Voorst, Robert E. (2000). Jesus Outside the New Testament: An Introduction to the Ancient Evidence. Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. ISBN978-0802843685.

Further reading

[edit]

- Syme, Ronald (1958). Tacitus. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN978-0-19-814327-7.

- Tacitus and the Writing of History by Ronald H. Martin 1981 ISBN 0-520-04427-4

- Tacitus’ Annals by Ronald Mellor 2010 Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-515192-5

.

…..Mara ben Sparion to his son on Jesus

Mara bar Serapion on Jesus

Mara bar Serapion was a Stoic philosopher from the Roman province of Syria. He is noted for a letter he wrote in Aramaic to his son, who was named Serapion.[1][2] The letter was composed sometime after 73 AD but before the 3rd century, and most scholars date it to shortly after 73 AD during the first century.[3] The letter may be an early non-Christian reference to the crucifixion of Jesus.[1][4]

The letter refers to the unjust treatment of “three wise men”: the murder of Socrates, the burning of Pythagoras, and the execution of “the wise king” of the Jews.[1][2] The author explains that in all three cases the wrongdoing resulted in the future punishment of those responsible by God and that when the wise are oppressed, not only does their wisdom triumph in the end, but God punishes their oppressors.[5]

The letter has been claimed to include no Christian themes[2][4] and many scholars consider Mara a pagan,[2][4][6][7] although some suggest he may have been a monotheist.[3] Some scholars see the reference to the execution of a “wise king” of the Jews as an early non-Christian reference to Jesus.[1][2][4] Criteria that support the non-Christian origin of the letter include the observation that “king of the Jews” was not a Christian title, and that the letter’s premise that Jesus lives on in his teachings he enacted is in contrast to the Christian concept that Jesus continues to live through his resurrection.[4][5]

Scholars such as Robert Van Voorst see little doubt that the reference to the execution of the “king of the Jews” is about the death of Jesus.[5] Others such as Craig A. Evans see less value in the letter, given its uncertain date, and the ambiguity in the reference.[8]

The passage and its context

[edit]

Mara Bar-Serapion’s letter is preserved in a 6th or 7th century manuscript (BL Add. 14658) held by the British Library, and was composed sometime between 73 AD and the 3rd century.[1] Nineteenth century records state that the manuscript containing this text was one of several manuscripts obtained by Henry Tattam from the monastery of St. Mary Deipara in the Nitrian Desert of Egypt and acquired by the Library in 1843.[9][10] William Cureton published an English translation in 1855.[11]

The beginning of the letter makes it clear that it is written to the author’s son: “Mara, son of Serapion, to my son Serapion, greetings.”[4] The key passage is as follows:

What else can we say, when the wise are forcibly dragged off by tyrants, their wisdom is captured by insults, and their minds are oppressed and without defense? What advantage did the Athenians gain from murdering Socrates? Famine and plague came upon them as a punishment for their crime. What advantage did the men of Samos gain from burning Pythagoras? In a moment their land was covered with sand.

What advantage did the Jews gain from executing their wise king? It was just after that their kingdom was abolished. God justly avenged these three wise men: the Athenians died of hunger; the Samians were overwhelmed by the sea and the Jews, desolate and driven from their own kingdom, live in complete dispersion. But Socrates is not dead, because of Plato; neither is Pythagoras, because of the statue of Juno; nor is the wise king, because of the “new law” he laid down.[5]

In this passage the author explains that when the wise are oppressed, not only does their wisdom triumph in the end, but God also punishes their oppressors.[5]

The context of the letter is that the Romans had destroyed Mara’s city in a war, taking him prisoner along with others. The letter was written from prison to encourage the author’s son to pursue wisdom. It takes the form of a set of rhetorical questions which ask about the benefits of persecuting wise men.[4][5]

Mara hints that the occupation of his land will in the end bring shame and disgrace on the Romans. His letter advises the pursuit of wisdom to face the difficulties of life.[5]

Historical analysis

The letter has been claimed to include no Christian themes and a number of leading scholars such as Sebastian Brock consider Mara a pagan.[2][4][6][7] A small number of scholars suggest that Mara may have been a monotheist.[3]

The non-Christian origin of the letter is supported by the observation that “king of the Jews” was not a Christian title during the time period the letter was written.[4][5] The statement in the letter that the wise king lives on because of the “new law” he laid down is also seen as an indication of its non-Christian origin, for it ignores the Christian belief that Jesus continues to live through his resurrection.[4][5] Another viewpoint is that he could be referring to the resurrection recorded in Jesus’s teachings which say he lived on, thus establishing his “new law” (possibly paralleling the “New Covenant“).[citation needed]

This means that it is impossible to infer if Mara believed the resurrection happened or not, and leaves it up to speculation whether he was a Christian or a non-Christian who agreed with Christians as regarding Jesus as a “wise king” according to the Gospels. Given that the gospel portraits of Jesus’ crucifixion place much of the blame for the execution of Jesus on the Roman procurator Pontius Pilate (with the Jewish mob merely acting as agitators), some Gospels do agree with the Jews being to blame.[4] And referring to “king of the Jews” rather than the Savior or Son of God indicates that the impressions of Bar-Serapion were not formed by Christian sources, although Jewish Christians did call him the king of the Jews.[4]

Theologian Robert Van Voorst sees little doubt that the reference to the execution of the “king of the Jews” is about the death of Jesus.[5] Van Voorst states that possible reasons for Bar-Serapion to suppress the name of Jesus from the letter include the ongoing persecutions of Christians at the time and his desire not to offend his Roman captors who also destroyed Jerusalem.[5] Others such as Craig A. Evans sees less value in the letter, given its uncertain date, and the possible ambiguity in the reference.[8]

Bruce Chilton states that Bar-Serapion reference to the “king of Jews” may be related to the INRI inscription on the cross of Jesus’ crucifixion, as in the Gospel of Mark (15:26 paragraph 1).[4] Van Voorst states that the parallels drawn between the unjust treatment of three men, and the destruction of Athens and Samos leads to the conclusion that Bar-Serapion viewed the destruction of Jerusalem as punishment for the Jewish rejection of Jesus.[5]

Evans, however, argues that unlike the references to Socrates and Pythagoras, bar Serapion does not explicitly mention Jesus by name, thereby rendering the actual identity of the “wise king” in the letter less than certain.[8]

The letter was written after the AD 72 annexation of Samosata by the Romans, but before the third century.[12] Most scholars date the letter to shortly after AD 73 during the first century.[3]

References

[edit]

- ^ a b c d e The Cradle, the Cross, and the Crown: An Introduction to the New Testament by Andreas J. Köstenberger, L. Scott Kellum 2009

ISBN 978-0-8054-4365-3 page 110

- ^ a b c d e f Evidence of Greek Philosophical Concepts in the Writings of Ephrem the Syrian by Ute Possekel 1999 ISBN 90-429-0759-2 pages 29-30

- ^ a b c d Van Voorst, Robert E (2000). Jesus Outside the New Testament: An Introduction to the Ancient Evidence. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN 0-8028-4368-9 pages 53-56

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Studying the Historical Jesus: Evaluations of the State of Current Research edited by Bruce Chilton, Craig A. Evans 1998 ISBN 90-04-11142-5 pages 455-457

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Jesus outside the New Testament: an introduction to the ancient evidence by Robert E. Van Voorst 2000 ISBN 0-8028-4368-9 pages 53-55

- ^ a b Sebastian Brock in The Cambridge Ancient History Volume 13 edited by Averil Cameron and Peter Garnsey (Jan 13, 1998) ISBN 0521302005 page 709

- ^ a b The Roman Near East, 31 B.C.-A.D. 337 by Fergus Millar ISBN 0674778863 page 507

- ^ a b c Jesus and His Contemporaries: Comparative Studies by Craig A. Evans 2001 ISBN 978-0-391-04118-9 page 41

- ^ Wright, W. (1872). Catalogue of the Syriac Manuscripts in the British Museum Acquired since the Year 1838, Volume III. Longmans & Company (printed by order of the Trustees of the British Museum). pp. xiii, 1159. “The manuscripts arrived at the British Museum on the first of March 1843, and this portion of the collection is now numbered Add. 14,425–14,739.” BL Add. 14,658 is included among these manuscripts.

- ^ Perry, Samuel Gideon F. (1867). An ancient Syriac document, purporting to be the record of the second Synod of Ephesus. Oxford: Printers to the University (privately printed). pp. v–vi.

- ^ Ross, Steven K. (2001). Roman Edessa: Politics and Culture on the Eastern Fringes of the Roman Empire. Psychology Press. p. 119. ISBN 9780415187879.

- ^ The Middle East under Rome by Maurice Sartre, Catherine Porter and Elizabeth Rawlings (Apr 22, 2005) ISBN 0674016831 page 293

Further reading

[edit]

- Cureton, William (1855). Spicilegium Syriacum: containing remains of Bardesan, Meliton, Ambrose and Mara Bar Serapion. Rivingstons. p. 70.

spicilegium Cureton.

- Merz, Annette; Tieleman, Teun L., eds. (2012). The Letter of Mara bar Sarapion in Context: Proceedings of the Symposium Held at Utrecht University, 10–12 December 2009. Brill.

- Ramelli, Ilaria (2010). “The Letter of Mara Bar Serapion in Context, Utrecht University, 10–12 December 2009”. Hugoye: Journal of Syriac Studies. 13 (1): 81–85.

https://photos.app.goo.gl/Rx6cPphEbvKJ7eME9

Alcuni passi del libro “Oltre il velo di Iside” di Alessandro De Angelis.

Molto accurato…incredibile.

Devo acquistare l’ultimo libro sulla discendenza di Gesù, sulla tomba dei suoi figli.

Questo è un lavoro da Titano e con una passione genuina :), ma i cosiddetti esperti di Storia(da propaganda)che lo demonizzano hanno patti con il denaro e con i Giudei.

Grazie. Probabilmente non sapremo mai cosa spinse Gesù a non avere uno scriba, un seguace istruito, che annotasse le Sue parole e i Suoi insegnamenti. Come seme stellare, fece del suo meglio per cercare di sollevare una razza folle, ma presto fu trasformato in un dio. E poi il dio dovrebbe compiere miracoli e salvarci. Questo è esattamente il motivo per cui gli alieni nordici si arresero: “Non vogliamo cambiare, sarebbe troppo difficile, di’ a te che il dio deve salvarci da noi stessi”.

Purtroppo è così 🙁