Sainte-Chapelle

Hard to imagine, but in 1248 many Frenchmen were blond, especially the nobility

| Sainte-Chapelle | |

|---|---|

Sainte-Chapelle, upper level interior

|

|

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Catholic Church |

| Province | Archdiocese of Paris |

| Region | Île-de-France |

| Rite | Roman Rite |

| Status | Secularized since French Revolution |

| Location | |

| Location | 10, boulevard du Palais, 1st arrondissement |

| Municipality | Paris |

| Country | France |

| Geographic coordinates | 48°51′19″N 2°20′42″E |

| Architecture | |

| Type | Royal chapel |

| Style | Rayonnant Gothic |

| Groundbreaking | 1242 |

| Completed | 1248 |

| Official name: Sainte-Chapelle | |

| Designated | 1862 |

| Reference no. | PA00086001[1] |

| Denomination | Église |

| Website | |

| www |

|

The Sainte-Chapelle (French: [sɛ̃tʃapɛl]; English: Holy Chapel) is a royal chapel in the Gothic style, within the medieval Palais de la Cité, the residence of the Kings of France until the 14th century, on the Île de la Cité in the River Seine in Paris, France.

Construction began sometime after 1238 and the chapel was consecrated on 26 April 1248.[2] The Sainte-Chapelle is considered among the highest achievements of the Rayonnant period of Gothic architecture. It was commissioned by King Louis IX of France to house his collection of Passion relics, including Christ’s Crown of Thorns – one of the most important relics in medieval Christendom. This was later held in the nearby Notre-Dame Cathedral until the 2019 fire, which it survived.[3]

Along with the Conciergerie, Sainte-Chapelle is one of the earliest surviving buildings of the Capetian royal palace on the Île de la Cité. Although damaged during the French Revolution and restored in the 19th century, it has one of the most extensive 13th-century stained glass collections anywhere in the world.

The chapel is now operated as a museum by the French Centre of National Monuments, along with the nearby Conciergerie, the other remaining vestige of the original palace.

History

[edit]

Construction of France

[edit]

Sainte-Chapelle was inspired by the earlier Carolingian royal chapels, notably the Palatine Chapel of Charlemagne at his palace in Aix-la-Chapelle (now Aachen). It was built in about 800 and served as the oratory of the Emperor. In 1238 Louis IX had already built one royal chapel, attached to the Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye. This earlier chapel had only one level; its plan, on a much grander scale, was adapted for Sainte-Chapelle. [4]

The two levels of the new chapel, equal in size, had entirely different purposes. The upper level, where the sacred relics were kept, was reserved exclusively for the royal family and their guests. The lower level was used by the courtiers, servants, and soldiers of the palace. It was a very large structure, 36 meters (118 ft) long, 17 meters (56 ft) wide, and 42.5 meters (139 ft) high, ranking in size with the new Gothic cathedrals in France. [4]

In addition to serving as a place of worship, the Sainte-Chapelle played an important role in the political and cultural ambitions of King Louis and his successors.[5][6] With the imperial throne at Constantinople occupied by a mere Count of Flanders and with the Holy Roman Empire in uneasy disarray, Louis’ artistic and architectural patronage helped to position him as the central monarch of western Christendom, the Sainte-Chapelle fitting into a long tradition of prestigious palace chapels. Just as the Emperor could pass privately from his palace into the Hagia Sophia in Constantinople, so now Louis could pass directly from his palace into the Sainte-Chapelle. More importantly, the two-story palace chapel had obvious similarities to Charlemagne‘s palatine chapel at Aachen (built 782–805)—a parallel that Louis was keen to exploit in presenting himself as a worthy successor to the first Holy Roman Emperor.[7] The presence of the fragment of the True Cross and crown of thorns gave enormous prestige to Louis IX. Pope Innocent IV proclaimed that it meant that Christ had symbolically crowned Louis with his own crown.[8]

The Royal Chapel

[edit]

-

Charter of foundation of the Sainte-Chapelle by Louis IX (1246)

-

Louis IX receives the crown of thorns and other sacred relics for the Sainte-Chapelle (14th century illustration)

-

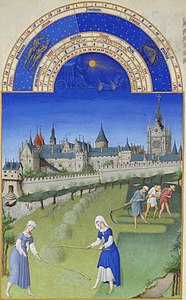

Illustration in Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry (c. 1500)

Sainte-Chapelle, in the courtyard of the royal palace on the Île de la Cité (now part of a later administrative complex known as La Conciergerie), was built to house Louis IX‘s collection of relics of Christ, which included the crown of thorns, the Image of Edessa, and some thirty other items. Louis purchased his Passion relics from Baldwin II, the Latin emperor at Constantinople, for the sum of 135,000 livres. This money was paid to the Venetians to whom the relics had been pawned.

The relics arrived in Paris in August 1239, carried from Venice by two Dominican friars. Upon arrival, King Louis hosted a week-long celebratory reception for the relics. For the final stage of their journey they were carried by Louis IX himself, barefoot and dressed as a penitent, a scene depicted in the Relics of the Passion window on the south side of the chapel. The relics were stored in a large and elaborate silver chest, the Grand-Chasse, on which Louis spent a further 100,000 livres.

The entire chapel, by contrast, cost 40,000 livres to build and glaze. Until it was completed in 1248, the relics were housed at chapels at the Château de Vincennes and a specially built chapel at the Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye. In 1246, fragments of the True Cross and the Holy Lance were added to Louis’s collection, along with other relics. The chapel was consecrated on 26 April 1248 and Louis’s relics were moved to their new home with great ceremony. Shortly afterward, the King departed on the Seventh Crusade, in which he was captured and later ransomed and released.[4] In 1704, the French composer Marc-Antoine Charpentier was buried in the chapel’s small cemetery, but this cemetery no longer exists.

The Parisian scholastic Jean de Jandun praised the building as one of Paris’ most beautiful structures in his “Tractatus de laudibus Parisius” (1323), citing:

that most beautiful of chapels, the chapel of the king, most decently situated within the walls of the king’s house, enjoys a complete and indissoluble structure of the most solid stone. The most excellent colors of the pictures, the precious gilding of the images, the beautiful transparence of the ruddy windows on all sides, the most beautiful cloths of the altars, the wondrous merits of the sanctuary, the figures of the reliquaries externally adorned with dazzling gems, bestow such a hyperbolic beauty on that house of prayer, that, in going into it below, one understandably believes oneself, as if rapt to heaven, to enter one of the best chambers of Paradise.

O how salutary prayers to the all-powerful God pour out in these oratories, when the internal and spiritual purities of those praying correspond proportionally with the external and physical elegance of the oratory!

O how peacefully to the most holy God the praises are sung in these tabernacles, when the hearts of those singers are by the pleasing pictures of the tabernacle analogically beautified with the virtues!

O how acceptable to the most glorious God appear the offerings on these altars, when the life of those sacrificing shines in correspondence with the gilded light of the altars![9]

Modifications (16th–18th century)

[edit]

-

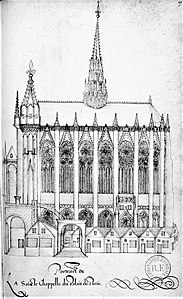

Sainte-Chapelle and the Palais de la Cité in 1615

-

View after the fire of 1630, which destroyed the spire of 1460

-

Louis XV departs a ceremony at the Palace, with Sainte-Chapelle behind (1715)

The chapel underwent considerable modification in the centuries that followed. A new two-story building, the Treasury of Chartres, was attached to the chapel on the north side shortly after it was completed. It remained until 1783, when it was demolished to build the new Palace of Justice. Another building, which served as a vestiary and sacristy, as well as residence for the guardian of the treasury, was placed on the north side. In the 15th century, Louis X of France built a monumental enclosed stairway from the courtyard on the south side to the upper level. This was damaged by fire in 1630, rebuilt, but finally demolished. Fires in the palace in 1630 and 1776 also caused considerable damage, especially to the furniture, and a flood in the winter of 1689–1690 caused major damage to the painted walls of the lower chapel. The original stained glass on the ground floor was removed, and the floor raised. The original ground floor glass was replaced by Gothic-style windows in the 19th century.[10]

Revolutionary vandalism (18th century)

[edit]

Sainte-Chapelle, as both a symbol of religion and royalty, was a prime target for vandalism during the French Revolution. The chapel was turned into a storehouse for grain, and the sculpture and royal emblems on the exterior were smashed.[11] The spire was pulled down. Some of the stained glass was broken or dispersed, but nearly two-thirds of the glass today is original; some of the original glass was relocated in other windows, The sacred relics were dispersed although some survive as the “relics of Sainte-Chapelle” in the treasury of Notre-Dame de Paris. Various reliquaries, including the grande châsse, were melted down for their precious metal.

Restoration (19th–21st century)

[edit]

-

Sainte-Chapelle in 1839, before restoration

-

The sculptor Adolphe-Victor Geoffroy-Dechaume with his archangel of the Passion and the head of another sculpture (1847)

-

A watercolour painting by Félix Duban used to guide the restorers (1847)

-

The chapel undergoing restoration (1841–67)

-

The lower chapel in 1900–1905

-

Upper chapel, 1890–1900

Between 1803 and 1837, the upper chapel was turned into a depository for the archives of the Palace of Justice next door.[12] The lower two meters (6 ft 7 in) of stained glass was removed to facilitate working light. Some of the glass was used to replace broken glass in other windows, and other panes were put on the market.[13] Beginning in 1835, scholars, archeologists and writers demanded that the church be preserved and restored to its medieval state. In 1840, under King Louis-Philippe, a long campaign of restoration began. It was first conducted by Félix Duban, then by Jean-Baptiste Lassus and Émile Boeswillwald, with the young Eugène Viollet-le-Duc as an assistant. The work continued for twenty-eight years, and served as a training ground for a generation of archeologists and restorers.[12] It was faithful to the original drawings and descriptions of the chapel that survived.[14]

The restoration of the stained glass was a parallel project, which lasted from 1846 until 1855, with the goal of returning the chapel to its original appearance. It was carried out by the glass craftsmen Antoine Lusson and Maréchal de Metz and the designer Louis Steinheil. About one third of the glass, added in later years, was removed and replaced with medieval glass from other sources, or with new glass made in the original Gothic style. Eighteen of the original panels are found today in the Musée de Cluny in Paris.[15]

The stained glass was removed and placed into safe storage during World War II. In 1945 a layer of external varnish had been applied to protect the glass from the dust and scratches of wartime bombing.[16] This had gradually darkened, making the already fading images even harder to see.[17] In 2008, a more comprehensive seven-year programme of restoration began, costing some €10 million to clean and preserve all the stained glass, clean the facade stonework and conserve and repair some of the sculptures. Half of the funding was provided by private donors, the other half coming from the Villum Foundation.[16] Included in the restoration was an innovative thermoformed glass layer applied outside the stained-glass windows for added protection. The restoration of the flamboyant rose window on the west facade was completed in 2015 in time for the 800th anniversary of the birth of St. Louis.[18]

Timeline

[edit]

- 1239 – Louis IX purchases the reputed Crown of Thorns

- 1241 – The crown and other relics arrive in Paris

- 1242-44 – Construction begins

- 1248 – Sainte-Chapelle completed and consecrated

- 1264-1267 – Installation of the tribune of relics

- 1379 – Charles V of France offers the Sainte-Chapelle Gospels to the treasury

- 1383 – First spire rebuilt

- End of 15th c. – Monumental exterior stairway built by Louis XII

- 1460 (approx.) 14th-century spire replaced

- 1485-1498 – west rose window installed

- 1630 – Fire damages spire and outer stairway

- 1690 – Flood damages lower chapel – original lower chapel stained glass removed

- 1793 – Revolutionaries smash portals and royal emblems. Chapel turned to civil use, and spire destroyed.

- 1803-1837 – Chapel becomes storeroom for files of Ministry of Justice

- 1805 – Relics of Passion transferred to Notre-Dame de Paris

- 1840-48 – Major restoration of chapel and decoration

- 1846-55 – Restoration and additions to stained glass windows

- 1853-55 – Current spire constructed

- 1862- Chapel is classified as an historical monument[a]

Description

[edit]

The royal chapel is a prime example of the phase of Gothic architectural style called “Rayonnant“, marked by its sense of weightlessness and strong vertical emphasis. It stands squarely upon a lower chapel, which served as parish church for all the inhabitants of the palace, which was the seat of government.

Exterior

[edit]

-

The church from the east

-

The south side. The upper walls are strengthened by buttresses and iron bars, allowing larger windows

-

Louis IX holding a fragment of the true cross

-

South facade

The contemporary visitor entering the courtyard of the Royal Palace would have been met by the sight of a grand ceremonial staircase (the Grands Degres) to their right and the north flank and eastern apse of the Sainte-Chapelle to their left. The chapel exterior shows many of the typical characteristics of Rayonnant architecture—deep buttresses surmounted by pinnacles, crocketted gables around the roof-line and vast windows subdivided by bar tracery. The internal division into upper and lower chapels is clearly marked on the outside by a string-course, the lower walls pierced by smaller windows with a distinctive spherical triangle shape. Despite its decoration, the exterior is relatively simple and austere, devoid of flying buttresses or major sculpture and giving little hint of the richness within.

No designer-builder is named in the archives concerned with the construction. In the 19th century it was assumed (as with so many buildings of medieval Paris) to be the work of the master mason Pierre de Montreuil, who worked on the remodelling of the Royal Abbey of Saint-Denis and completed the south transept façade of Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris.[19] Modern scholarship rejects this attribution in favour of Jean de Chelles or Thomas de Cormont, while Robert Branner saw in the design the hand of an unidentified master mason from Amiens.[20]

The Sainte-Chapelle’s most obvious architectural precursors include the apsidal chapels of Amiens Cathedral, which it resembles in its general form, and the Bishop’s Chapel (c. 1180s) of Noyon Cathedral, from which it borrowed the two-story design. a major influence on its overall design may have come from contemporary metalwork, particularly the precious shrines and reliquaries made by Mosan goldsmiths.[20]

Though the buttresses are substantial, they are too close to the vault to counter its side thrust. Metal elements such as iron rods or chains, able to support tension, were used to replace the flying buttresses of previous structures.

West front

[edit]

-

The west front with rose window

-

Detail of the flamboyant rose window

-

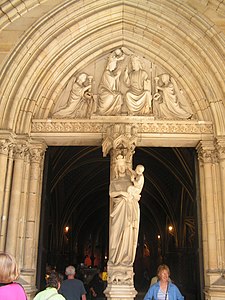

Portal of the lower chapel

-

Portal of the upper chapel

-

Gable of the west front

The west front is composed of a porch two levels high, beneath a flamboyant Gothic rose window installed in the upper chapel in the 15th century. At the top is a pointed arch an oculus window, and a balustrade around the bottom of the roof, decorated with interlaced fleur-de-lys emblems placed by Charles V of France. On either side of the porch are towers which contain the narrow winding stairways to the upper chapel, and which also hide the buttresses. The spires of the towers are also decorated with royal fleur-des-lys beneath a sculpted crown of thorns. This decoration dates to the 15th century, and was restored in about 1850 by Geoffroy-Dechaume.[21]

The portal of the upper chapel is located on the balcony of the upper level. The original sculpture of the west portal was smashed during the Revolution. It was restored by Geoffroy-Dechaume between 1854 and 1873.[21]

Spire

[edit]

-

The spire in the 16th century

-

19th-century spire

-

Detail of the spire

The current spire, thirty-three meters (108 ft) high, is the fifth to be built at Sainte-Chapelle since the 13th century. The appearance of the first is unknown, but the second, built in 1383 under Charles V, is pictured in an illustration of the Tres Riches Heures du Duc de Berry.[21] He replaced it with another in about 1460, but this spire burned in 1630. It was replaced by another, which was destroyed following the French Revolution in 1793. The present spire was built of cedar wood by the architect Lassus beginning in 1852. The sculpture decorating the spire was designed in 1853 by Geoffroy-Dechaume. The painter-designer Steinheil designed the sculpture at the base of the spire, and his face appears as two of the apostles, Saint Thomas and Saint Bartholomew. Above the gables are statues representing angels carrying the instruments of The Passion. Above the chevet is a statue of the Archangel Michael slaying a dragon. Around the feet of the archangel are sculptures, also designed by Geoffroy-Dechaume, of eight persons, portrayed by workers of the reconstruction, laying wreaths at the Archangel’s feet.[21]

Interior

[edit]

-

Plan of the lower chapel (front) and upper chapel (right)

Saint Chapelle, built to house a reliquary, was itself like a precious reliquary turned inside out (with the richest decoration on the inside).[22] Although the interior is dominated by the stained glass (see below), every inch of the remaining wall surface and the vault was also richly coloured and decorated. Analysis of remaining paint fragments reveals that the original colours were much brighter than those favoured by the 19th-century restorers and would have been closer to the colours of the stained glass. The quatrefoils of the dado arcade were painted with scenes of saints and martyrs and inset with painted and gilded glass, emulating Limoges enamels, while rich textiles hangings added to the richness of the interior.

The most striking aspect and original feature of the plan is the nearly total absence of masonry walls in the upper chapel. The walls are replaced by pillars and buttresses, and the space between is almost entirely glass, filling the upper chapel with light.[23]

Lower Chapel

[edit]

-

Lower chapel, with statue of Louis IX

-

Ceiling of the lower chapel. Small gilded flying buttresses reinforce the arches

-

The lower chapel, with the Fleur-de-Lys of Louis IX (symbol from his French Capet royal family heritage) and the castle, (symbol of the Spanish royal family of his mother, Blanche of Castile), decorating the columns

The lower chapel was dedicated to the Virgin Mary, and was used by the non-royal inhabitants of the neighbouring Royal Palace. The portal of the chapel represents the Virgin Mary as a column statue. The portal, and almost all the decoration of the chapel, was created by Geoffroy-Duchaume between 1854 and 1858. The primary decorative themes of the sculpture, columns and murals are the Fleur-de-Lys emblem of Louis IX and a stylised castle, the coat of arms of Blanche of Castile, the mother of Louis IX.[24]

The lower chapel is only 6.6 meters (22 ft) high, with a six-meter wide central vessel and two narrow side aisles. The supports of the ceiling vaults are unusual; the outward thrust of the vaults is counterbalanced by small, elegant arched buttresses between the outer and inner columns, and they are also reinforced by a metallic structure hidden under the paint and plaster.[24]

The one-hundred forty capitals of the columns are an important decorative feature; they are from the mid-13th century, and predate the columns of the upper chapel. They have floral decoration of acanthus leaves typical of the period. Each of the gilded leaves corresponds with a slender colonette above, which rises upward to support the vaults. The columns are painted with alternating floral designs and the castle emblem of Castile. The red, gold and blue painting dates to the 19th century restoration.[24]

The original stained glass of the lower chapel was destroyed by a flood in 1690; it was replaced by colourless glass. The present glass depicts scenes from the life of the Virgin Mary, surrounded by grisaille glass, while the apse has more elaborate and colourful scenes from the Virgin’s life. All the windows were designed by Steinheil during the 19th century restoration. The lower chapel originally had a doorway to the sacristy on the left lateral traverse. Since it could not have a window, it was decorated in the 13th century with a mural of the Annunciation. This was rediscovered during the 19th-century work, and restored by Steinheil.[25]

Upper Chapel

[edit]

-

The apse of the upper chapel

-

The Chasse, which held the sacred relics

-

Later flamboyant rose window

-

South and North walls

The upper chapel is reached by narrow stairways in the towers from lower level. The structure is simple; a rectangle 33 by 10.7 meters (108 by 35 ft), with four traverses and an apse at the east end with seven bays of windows. The most striking features are the walls, which appear to be almost entirely made of stained glass; a total of 670 square meters (7,200 sq ft) of glass, not counting the rose window at the west end. This was a clever illusion created by the master builder; each vertical support of the windows is composed of seven slender columns, which disguise their full thickness. In addition, the walls and windows are braced on the exterior by two belts of iron chain, one at the mid-level of the bays and the other at the top of the lancets; these are hidden behind the bars holding the stained glass. Additional metal supports are hidden under the eaves of the roof to brace the windows against the wind or other stress. Furthermore, the windows of the nave are slightly higher than the windows in the apse (15.5 meters, 51 ft compared with 13.7 meters, 45 ft), making the chapel appear longer than it actually is.[26]

There are two small alcoves set into the walls on the third traverse of the chapel, with archivolts or arches richly decorated above with painting and sculpture of angels. These were the places where the King and Queen worshipped during religious services; the King on the north side, the Queen on the south.[27]

Vaults of the upper chapel

[edit]

-

Vaults of the apse (Note the fleur-de-lis symbol, inherited from the Capet line of Louis IX‘s father, Louis VIII Capet, of France)

-

Vaults of the upper chapel

Stained glass

[edit]

-

Scenes from Passion of Christ (apse) (click 2X for full-size)

-

Scenes from life of Ezekiel (south wall)

-

Scenes from Ezekiel and Job (south wall, bay 4)

-

Saint Louis transports relics of the true cross (south wall, bay 14)

-

Genesis – God creates plants and trees (south wall, bay 9 – restored)

The most famous features of the chapel, among the finest of their type in the world, are the fifteen great stained-glass windows in the nave and apse of the upper chapel, which date from the mid-13th century, as well as the later rose window (put in place in the 15th century). The stone wall surface is reduced to little more than a delicate framework. The thousands of small pieces of glass turn the walls into great screens of coloured light, largely deep blues and reds, which gradually change in intensity from hour to hour.[28]

Most of the windows were put into place between 1242 and 1248. The names of the glass artists are unknown, but the art historian Louis Grodecki identified what appear to be three different ateliers with different styles. The windows in the apse and most of the windows on the north wall of the nave are made by one workshop. These works are known for supple forms and costumes, with simplified features. The second workshop, named by Grodecki as Master of the Ezekiel window, made the Ezekiel and Daniel windows, as well as the window of the Kings. That work is characterized by elongated forms, and more elaborate and angular draperies. The third artist or workshop is called the Master of Judith and Esther, for the distinct style of those windows, as well as the window of Job. They are distinguished by more subtle details in the faces, and a resemblance to the figures in illuminated manuscripts.[29]

Despite some damage the windows display a clear iconographical programme. The three windows of the eastern apse illustrate the New Testament, featuring scenes of The Passion (centre) with the Infancy of Christ (left) and the Life of John the Evangelist (right). By contrast, the windows of the nave are dominated by Old Testament exemplars of ideal kingship/queenship in an obvious nod to their royal patrons. The cycle starts at the western bay of the north wall with scenes from the Book of Genesis (heavily restored). The next ten windows of the nave follow clockwise with scenes from Exodus, Joseph, Numbers/Leviticus, Joshua/Deuteronomy, Judges, (moving to the south wall) Jeremiah/Tobias, Judith/Job, Esther, David and the Book of Kings. The final window, occupying the westernmost bay of the south wall brings this narrative of sacral kingship right up to date with a series of scenes showing the rediscovery of Christ’s relics, the miracles they performed, and their relocation to Paris in the hands of King Louis himself.[30]

The west rose window

[edit]

-

Centerpiece- vision of the seven candlesticks

-

Adoration of the beast

-

The chapel’s flamboyant west rose window

-

First horseman of the Apocalypse

-

Detail of rose window; souls under the altar

The rose window at the west of the upper chapel was made in the late 15th century, later than the other windows. It is a very fine example of the flamboyant Gothic style, named for the flamelike curling designs. It is nine meters in diameter, and is composed of eighty-nine separate panels representing scenes of the Apocalypse. The 15th-century glass artists used a new technique, called silver stain, which allowed them to paint on the glass with enamel paints, and to use fire to fuse the paint onto the glass. This allowed them to modify the color, and create shading and other fine details. It was thoroughly cleaned in 2014–15, giving it greater brightness and clarity.[31]

Stained glass from Saint-Chapelle in other museums

[edit]

Some of the early stained glass that was removed from Saint-Chapelle is now found in the other museums, including the National Museum of the Middle Ages, or Musee de Cluny, in Paris and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.

-

Detail of a stained-glass window depicting a baptism (late 12th century) (Musée de Cluny)

-

The Resurrection of the dead (late 12th century) (Musée de Cluny)

-

King Saul and David (late 12th century) (Musée de Cluny)

-

Daniel and Dream of Nebuchadnezzar (late 12th century) (Musée de Cluny)

-

Scene from Book of Ezekiel (mid 12th century) (Victoria and Albert Museum)

Art and decoration

[edit]

Sculpture

[edit]

-

Detail of the portal of the upper chapel; Christ and the Last Judgement by Geoffroy-Dechaume

-

The creation of Eve from Adam’s rib (portal of upper chapel)

-

Relief sculpture of Noah’s ark and the flood (portal of upper chapel)

Most of the sculpture of the portals was destroyed during the French Revolution, but between 1855 and 1870 the sculptor Adolphe-Victor Geoffroy-Dechaume was able to recreate it, using 18th century descriptions and engravings. One of the major works he recreated was the tympanum over the portal of the upper chapel, with a figure of Christ giving a blessing, with the Virgin Mary and John the Baptist alongside him. Two angels are behind him, holding the crown of thorns and the cross, the most famous relics of the chapel. On the lintel below, the sculpture depicts Saint Michael weighing the souls of the dead, with those sent to heaven on the left and those damned on the right.[26] Sculpted Biblical scenes from the Old Testament fill the panels on lower walls, including the Creation and Noah’s ark. They were made by Geoffroy-Dechaume in 1869–70.

-

Carved angel on the alcove of the King, north wall

-

Carved angels holding crown of thorns in the apse (13th century)

-

Sculpture above the alcove of the King, upper chapel (13th c.)

-

Sculpture above the alcove of the Queen, upper chapel (13th c.)

While most of the sculpture on the exterior dates to the 19th century, the apse of the upper chapel contains a number of original 12th century statues, which, unlike the exterior statues, were polychrome. Traces of color were found during the restoration in the 19th century, and the statues were restored to include those colors. The arches of the tribune in the apse at the east end, where the case of sacred relics was placed, is ornamented with the original polychrome angels from the 13th century.[32]

-

One of the Apostles

-

Statue of Louis IX (Note the fleur-de-lis and castle symbols on the columns, symbolic of his royal ancestry through his parents, Louis VIII Capet of France, and Blanche of Castile.)

-

Sculpture on north wall of upper chapel

-

One of the Apostles, north wall

-

St. John, undecorated (now in the Museum of the Middle Ages Hotel de Cluny)

-

An Apostle, north wall

The upper chapel walls also displayed a group of sixteen statues of the Apostles, which date to about 1240. Some portray the apostles in simple classical costumes and bare feet, while others are polychrome and have much more elaborate clerical costumes. Some of these statues are now found in the collection of the National Museum of the Middle Ages in the Musée de Cluny.

Painting

[edit]

-

Lower chapel, column capital on reverse of west front. Castles and fleur-de-lis symbols seen here on the columns, are found throughout the chapel, relating to the two royal families from which Louis IX descended (the Capet fleur-de-lis through his father, Louis VIII of France, and the Castile castle through his mother, Blanche of Castile).

-

Interior of the west facade; Christ with Angels, Sts. Isaiah and Jeremiah in the quadrilobes (painting by Steinheil, 1856)

-

Wall decoration, with fleur-de-lis in the background, and the castle symbol of the Kingdom of Castile in the foreground. Throughout the chapel, symbols of fleur-de-lis and castles are found repeatedly, in a nod to Louis IX’s royal heritage (the fleur-de-lis of the French Capet family through his father, Louis VIII, and the castle of the royal Spanish Castile family, the royal heritage of his mother, Blanche of Castile).

-

Quadrilobe painting of martyrdom of an Apostle, upper chapel (19th c. restitution of 13th c. decor)

The goal of the two principal architects of the 19th century restoration, Durban and Lassus, was to recreate the interior, as much as possible, as it appeared in the 13th century. They collected traces of the original polychrome paint from the columns, and in 1842 presented a comprehensive plan for interior decoration. In the soubassements, the lower portions where no traces of original color were found, they used a neutral tone, to avoid conflicting with the colors of the stained glass windows. For their palette of colors on other decoration, they drew upon the illuminations of a 13th-century book of Psalm from the Royal Library. They systematically repainted the forty-four 13th-century quadrilobe medallions on the stone arches of the soubassements, which depicted the martyrdom of saints presented against a gilded background. In 1845 Steinheil continued by repainting all of the medallions of the nave, with the exception of those in the two royal alcoves, following the original compositions. In 1983 the Service of Historic Monuments cleaned four of the medallions which had not been restored, and un-restored two which had been repainted, to study the original traces of paint from before 1845.[33]

The relics and the reliquary

[edit]

-

Louis IX places the crown of thorns at Sainte-Chapelle (illuminated manuscript from 1480s)

-

The Grande Châsse, or reliquary, in 1790

-

Crown of Thorns in gilded crystal case (Notre-Dame de Paris, now in Louvre)

-

Reliquary bust of Louis IX (Notre-Dame de Paris)

The principal relics for which the chapel was built were the crown of thorns, believed to have been worn by Christ during his Passion, and a small piece of the cross on which he was crucified. These were found in Constantinople, which had been captured by the Crusaders in 1204, and was then ruled by Baudouin II of Cortenay. Baudouin agreed to sell the crown for 135,000 livres, which went primarily to Venetian bankers, to whom he had mortgaged the crown to pay for the defence of the city. By purchasing the crown, Louis gained the prestige of funding the conquest of Constantinople, as well as displaying his personal devotion. The crown arrived in August 1239 and was placed in the earlier royal chapel of St. Nicholas, near the palace. Two years later, he made an additional purchase from Baudouin of a piece of the true cross and other relics related to the Passion, which were brought to Paris in September 1241. Thereafter, on each Holy Friday, the day of the Crucifixion, he conducted a solemn ceremony at Sainte-Chapelle, in which the relic was brought out and displayed to the faithful.[12]

The King had a large chasse made to hold and display the sacred objects. This was a case, open on the front, 2.7 meters (8 ft 10 in) long, made of silver and gilded copper. Each of the individual objects had its own case of precious metal with jewels. This was originally placed above the altar, but between 1264 and 1267, it was placed atop a high tribune in the apse of the church, where everyone could see it. In 1306, a new sacred relic was added: a portion of the skull of Louis himself, since he had been declared a saint.[34]

During the French Revolution, the Chasse and the vessels holding the relics were taken apart and melted down for their jewels and precious metals. The fragment of the cross was transferred first in 1793 to a collection of antiquities, then given to the Bishop of Paris. A new reliquary of gold and crystal was made for the crown of thorns. Since the Concordat of 1801, it was displayed in the treasury of the cathedral of Notre Dame de Paris,[34] but it was saved from the Notre-Dame de Paris fire on 15 April 2019 and has since been kept in the Louvre Museum.[35]

Organ

[edit]

-

The late 16th-century organ by Jacques Cellier

An organ is attested from the beginning; it was replaced in 1493, 1550 and 1762. it was not until July 1791 when the organ was transferred from the Sainte-Chapelle to Saint-Germain l’Auxerrois due to the French Revolution. The organ was built by François-Henri Clicquot, in a case designed by Pierre-Noël Rousset in 1752. However, its Neoclassical style seems to some writers to be too modern for that date.

Other Saintes-Chapelles

[edit]

Prior to the dissolution of the Sainte-Chapelle in 1803, following the French Revolution, the term “Sainte-Chapelle royale” also referred not only to the building but to the chapelle itself, the choir of Sainte-Chapelle. However, the term was also applied to a number of other buildings. Louis IX’s chapel inspired several “copies”, in the sense of royal or ducal chapels of broadly similar architectural form, built to house relics, particularly fragments of Louis’ Passion Relics given by the King.[36] Such chapels were normally attached to a ducal palace (e.g. Bourges, Riom), or else to an Abbey with particular links to the royal family (e.g. St-Germer-de-Fly). As with the original, such Holy Chapels were nearly always additional to the regular palatine or abbatial chapel, with their own dedicated clergy—usually established as a college of canons.[37] For the patrons, such chapels served not only as public expressions of personal piety but also as valuable diplomatic tools, encouraging important visitors to come and venerate their relics and showing their connection to the French crown. Notable Saintes-Chapelles in France include:

- Bourbon-l’Archambault: Founded c. 1310 by Louis IX’s grandson, Duke Louis I de Bourbon to house a fragment of the True Cross

- Chambéry: Founded c. 1400

- Châteaudun: Founded 1451

- Bourges: Founded 1392 by Duke Jean de Berry decorated with sculptures and stained glass by André Beauneveu. Now destroyed.

- Riom: Founded 1382 by Jean de Berry

- Saint-Germer-de-Fly Abbey: A very similar structure, also called the Sainte-Chapelle, was erected twelve years after the Paris chapel as an addition to the abbey church.

- Vincennes: Founded 1379 at one of the favourite Valois royal palaces by Charles V

- Vivier-en-Brie: Founded 1358 by the future Charles V while he was still the Dauphin

As the status of Saint Louis grew among Europe’s aristocracy, the influence of his famous chapel also extended beyond France, with important copies at Karlštejn Castle near Prague (c. 1360), the Hofburgkapelle in Vienna (consecrated 1449), Collegiate Church of the Holy Cross and St. Bartholomew, Wrocław (c. 1350) and Exeter College, Oxford (1860).

See also

[edit]

- French Gothic architecture

- French Gothic stained glass windows

- Gothic architecture

- Gothic cathedrals and churches

- List of historic churches in Paris

- Lady Leng Memorial Chapel

- List of tourist attractions in Paris

References

[edit]

Notes

[edit]

- ^ Events and dates of timeline from de Finance 2012, p. 49

Citations

[edit]

- ^ Ministry of Culture, Mérimée PA00086001 Sainte-Chapelle(in French)

- ^ Alain Erlande-Brandenburg, the Ste Chapelle (Paris-Buildings) in Grove Encyclopedia of Art

- ^ “Paris facts”. Paris Digest. 2018. Retrieved 19 September 2018.

- ^ Jump up to:abc de Finance 2012, p. 6.

- ^ Brenk, Beat (1995). “The Sainte Chapelle as a Capetian Political Program”. In Raguin, Virginia Chieffo; Brush, Kathryn; Draper, Peter (eds.). Artistic integration in Gothic buildings. University of Toronto Press. pp. 195–213. ISBN978-1-4426-7104-1.

- ^ Cohen, Meredith (2008). “An Indulgence for the Visitor: The Public at the Sainte-Chapelle of Paris”. Speculum. 83 (4): 840–883. doi:10.1017/S003871340001705X. S2CID162738720.

- ^ Daniel H. Weiss, Architectural Symbolism and the Decoration of the Ste.-Chapelle, in The Art Bulletin, Vol. 77, No. 2 (Jun. 1995), pp. 308-320, esp. p.317 n.45

- ^ Watkin, David, “A History of Western Architecture” (1986), p. 136

- ^ Erik Inglis, “Gothic Architecture and a Scholastic: Jean de Jandun’s Tractatus de laudibus Parisius (1323),” Gesta, XLII/1 (2003), 63-85.

- ^ de Finance 2012, pp. 12–13.

- ^ de Finance 2012, p. 13.

- ^ Jump up to:abc de Finance 2012, p. 14.

- ^ The Philadelphia Museum of Art conserves three panels from the “Judith” window, identified by M. Caviness, “Three medallions of stained glass from the Sainte-Chapelle of Paris”, Bulletin of the Philadelphia Museum of Art62 (July–September 1967:249-55).

- ^ Viollet-le-Duc, Dictionnaire, s.v. “Restauration”, “Vitrail”; a modern reassessment of the stained-glass restorations, in the context of the Gothic Revival, is in Alyce A. Jordan, “Rationalizing the Narrative: Theory and Practice in the Nineteenth-Century Restoration of the Windows of the Sainte-Chapelle”, Gesta37.2, Essays on Stained Glass in Memory of Jane Hayward (1918–1994) (1998:192-200).

- ^ de Finance 2012, p. 16.

- ^ Jump up to:ab Clavel, Sylvie (2009). The stained-glass windows of the Sainte-Chapelle, Paris(PDF) (Report). The Villum Foundation Annual Review, 2009. Archived from the original(PDF) on 24 January 2023. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

- ^ “Sainte-Chapelle, Paris”. Centre des monuments nationaux: Discovery Area. 2016. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

- ^ “Laser surgery restores Sainte-Chapelle stained glass window to Gothic glory”. The Guardian. 20 May 2015.

- ^ Robert Suckale, Pierre de Montreuil in Les Bâtisseurs des cathédrales gothiques, Strasbourg, 1989, pp.181–85

- ^ Jump up to:ab Branner 1966.

- ^ Jump up to:abcd de Finance 2012, p. 22.

- ^ Branner, Robert (1966), St Louis and the Court Style in Gothic Architecture, p. 8ff

- ^ de Finance 2012, p. 34.

- ^ Jump up to:abc de Finance 2012, pp. 26–27.

- ^ de Finance 2012, pp. 26–31.

- ^ Jump up to:ab de Finance 2012, pp. 34–35.

- ^ de Finance 2012, pp. 36–37.

- ^ de Finance 2012, p. 44.

- ^ de Finance 2012, p. 49.

- ^ Les Vitraux de Notre-Dame et de la Sainte-Chapelle de Paris, Corpus Vitrearum Media Aevi, Vol.1, Paris, 1959

- ^ de Finance 2012, pp. 62–63.

- ^ de Finance 2012, pp. 37–39.

- ^ de Finance 2012, pp. 40–41.

- ^ Jump up to:ab de Finance 2012, p. 15.

- ^ Clicquot, Athénaïs (9 September 2019). “Notre-Dame : la couronne d’épines à nouveau présentée à la vénération des fidèles” (in French). Retrieved 15 September 2020.

- ^ I. Hacker-Sück: La Sainte-Chapelle et les chapelles palatines du moyen âge en France, in Cahiers Archéologiques, Vol.13, 1962, pp.217–57

- ^ Robert Branner, The Sainte-Chapelle and the Capella regis in the Thirteenth Century, in Gesta, Vol.10, 1971, pp.19–22

Bibliography

[edit]

- Brisac, Catherine (1994). Le Vitrail (in French). Paris: La Martinière. ISBN2-73-242117-0.boom

- de Finance, Laurence (2012). La Sainte-Chapelle- Palais de la Cité (in French). Éditions du Patrimoine, Centre des Monuments Nationaux. ISBN978-2-7577-0246-8.

Further reading

[edit]

- Cavicchi, Camilla (2019). “Origin and Dissemination of Images of the Saint Chapel”. Music in Art: International Journal for Music Iconography. 44 (1–2): 57–77. ISSN1522-7464.

- Gebelin, F. (1937) La Sainte Chapelle et la Conciergerie. Paris.

- Smith, Elizabeth Bradford. (2015). ‘All my stained glass which I brought from Europe’: William Poyntell and the Sainte-Chapelle medallions.” Journal of the History of Collections. V.27 (November): 323–334.

External links

[edit]

.

.

……Louis IX, France’s greatest and most antisemitic king

Leave a Reply