What the CNN article does not say, the Jeff Zucker-run network being infamous for its sins of omission, is that Warne attacked tennis champion Novak Djokovic for refusing to get the vaxx. Warne got the jew vaxx and the booster — and now he is dead at 52.

Novak is a great tennis player & one of the all time greats. No doubt. But he’s lied on entry forms, been out in public when he knew he had covid & is now facing legal cases. He’s entitled to not be jabbed but Oz is entitled to throw him out ! Agree ? #shambles

— Shane Warne (@ShaneWarne) January 13, 2022

https://edition.cnn.com/2022/03/04/sport/shane-warne-death-spt-intl/index.html

How often have we seen celebrities bully others and virtue-signal that they got vaxxed and then keel over dead?

Instant karma.

It is the cheapest sort of bravado to speak out in total, slavish conformity with what the government, media and the Big Jews want you to say.

As Steve Kirsch reports:

The evidence

The evidence of harm has been hiding in plain sight including:

- An estimated reportable adverse event rate of 20% of those fully vaccinated (there are over 200M vaccinated, 1M VAERS reports and VAERS is at least 41X underreported)

- An estimated death due to vaccine of over 150K Americans

-

Embalmers reporting up to 93% of cases have telltale blood clots associated with the vaccine

- Blood before/after vaccination is visually very different

- Rates of myocarditis as high as 2% (Monte Vista Christian School and a private conversation with a DoD doctor)

- Rates of neurological damage as high as 4.5% (Israeli MOH survey).

- A minimum of 30% (Peter Schirmacher’s study) to 93% (Bhakdi’s study) of deaths post vaccine attributed to the vaccine

- A post-marketing survey disclosed by Pfizer that is pretty consistent with the VAERS data reports (I’ll write a separate substack on this later, but I didn’t see any smoking gun that isn’t already in VAERS where we already knew about thousands of adverse event types).

- An estimate of deaths and URF by Joel Smalley using death data in Massachusetts that confirms earlier numbers. Joel calculated a URF of 41, matching mine exactly! He also calculated a deaths per million doses (dpmd) of 945 which is even higher than the 411 dpmd calculated by Mathew Crawford.

- The Skidmore paper, “How Many People Died from the Covid-19 Inoculations? An Estimate Based on a Survey of the United States Population,” which estimated 294,000 excess deaths from the vaccine.

- German insurance company data estimate done by Mathew Crawford yielding an estimate of 120,000 deaths in the US caused by the vaccines

- Troubling anecdotal reports

…..Here is the study on spike proteins destroying DNA, by two Chinese scientists

The binary weapon extermination plot becomes clear: mRNA spike protein injections suppress DNA repair, followed by global nuclear events that unleash DNA-damaging radiation

Friday, March 04, 2022 by: Mike Adams

Tags: binary weapon, biological terrorism, biological weapons, biowar, chromosomes, depopulation, DNA, DNA repair, Double Strand Breaks, extermination, ionizing radiation, mRNA, NHEJ, nuclear, nuclear bombs, nuclear war, radiation, terrorism

This article may contain statements that reflect the opinion of the author

(Natural News) It is now becoming abundantly obvious what the next phase is going to be for achieving global depopulation. The vaccine bioweapon phase has achieved some level of morbid “success” in the eyes of the globalists, likely killing 1 – 2 billion human beings over the next decade as the spike protein damage takes its toll. But even this is nowhere near enough for the demonic entities controlling our planet, as they seek something closer to a 90% total reduction of the human population.

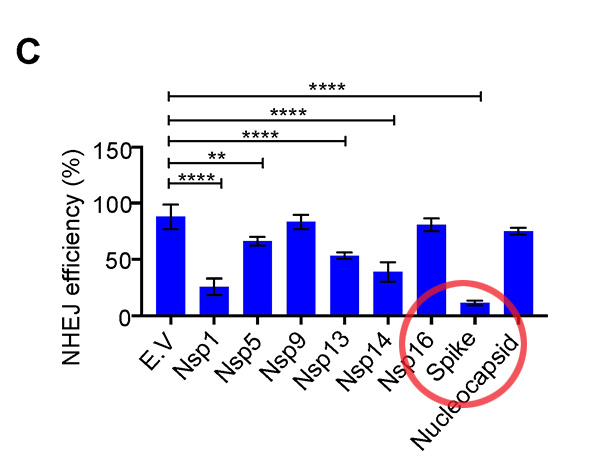

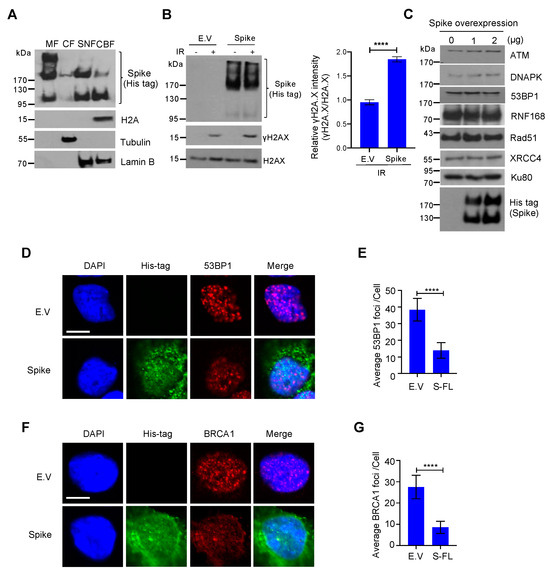

Suddenly their strategy is crystal clear. The spike protein mRNA injections cause about a 90% suppression of the DNA repair mechanism known as NHEJ – Non-Homologous End-Joining. This is a cellular mechanism that exists inside the cells of humans, animals and plants to maintain genetic integrity — a necessary condition for life.

Because of the NHEJ mechanism, we are able to automatically repair Double Strand Breaks (DSBs) in our chromosomes when we are subjected to ionizing radiation. Common sources of ionizing radiation include sunlight exposure, commercial jet flights and mammograms. When our NHEJ engine is working normally, chromosomes damaged by ionizing radiation are repaired and do not become cancer tumors. But when NHEJ is suppressed, the body cannot repair DNA damage and begins to grow micro tumors.

The following chart is taken from the bombshell NHEJ suppression study published in the journal Viruses. You can find it here. It shows the near-90 percent suppression of NHEJ in the presence of the spike protein which we now knows penetrates the nucleus of the cell.

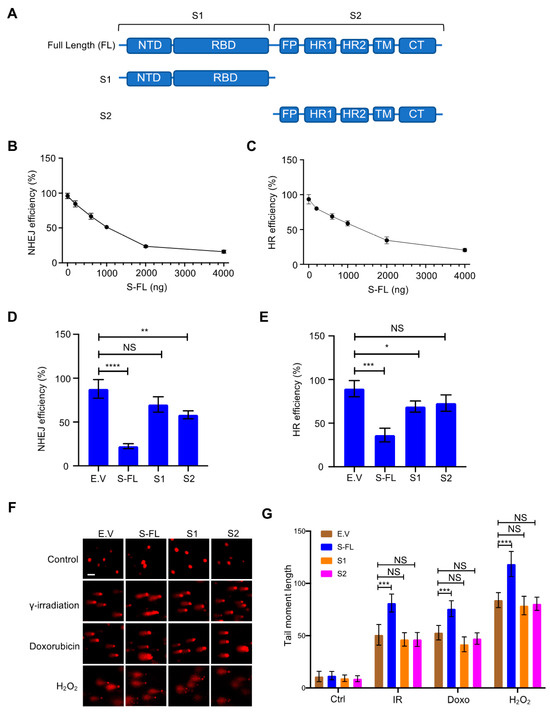

In the conclusion of the paper, the authors write, “We found that the spike protein markedly inhibited both BRCA1 and 53BP1 foci formation (Figure 3D–G). Together, these data show that the SARS–CoV–2 full–length spike protein inhibits DNA damage repair by hindering DNA repair protein recruitment.”

Micro tumors, over time — and especially in the toxic blood environment of the average vitamin D-deficient person — become large tumors. And those tumors lead to death (sometimes death by chemotherapy).

Five billion people now injected with mRNA gene therapy can be easily killed with low levels of ionizing radiation from ANY source

So right now, all across the world, there are about five billion people who have received covid vaccination injections (source) which are actually experimental gene therapy treatments that alter their DNA and suppress their DNA repair mechanisms. All that is necessary for globalists to kill those five billion people is to unleash a new source of low-level ionizing radiation that circulates across the globe… and then let physics do the rest.

Starting to get the picture of how evil these globalists really are?

This nefarious goal can be achieved by the globalists in any of the following ways:

- Unleashing a new nuclear “accident” in Ukraine or anywhere else.

- Setting off a nuclear bomb anywhere in the Northern hemisphere, including doing so as a false flag event to blame Russia.

- Detonating a dirty bomb anywhere in the Northern hemisphere, potentially as an act of nuclear terrorism.

In any of these three scenarios, ionizing radiation is released and spreads across the globe due to winds. Various radioisotopes likely to be released in these events include iodine-131, cesium-137, strontium-90, plutonium-241 and others. These isotopes have various half-lives that will unleash intense iodine-131 exposure for about 10 weeks or so, followed by cesium-137 which will contaminate soils, waterways and the food supply for about 300 years (that’s about 10 half-lives). Strontium-90 has a similar half life and decay time.

No one will be able to escape the radiation exposure in the Northern hemisphere.

When mRNA vaccinated people are exposed to low levels of ionizing radiation, they will immediately start growing a swarm of new micro tumors across their entire body

A normal, healthy person with functioning NHEJ can repair ionizing radiation damage, especially if the exposure is spread out over time. But mRNA vaccinated people have lost around 90% of that repair capability. This is why mRNA-injected people are already experiencing 2000% increases in cancer rates, anecdotally reported, and it’s why we’re seeing shocking increases in all-cause mortality as reported by several life insurance providers.

The addition of a new source of global, low-level ionizing radiation would be devastating to those who have taken the mRNA injections. They would lose genetic integrity across their bodies, with tissues and organs mutating into non-functioning attempts at blood vessels and protein strands. In effect, these people’s own cells would turn against them, and it wouldn’t be long before they would suffer catastrophic failures of one or more organs or organ systems such as the circulatory system. During autopsies, it would appear as if their bodies were ravaged by a sudden wave of cancer (similar to acute radiation poisoning, but acting more slowly).

Importantly, these deaths would be diagnosed as cancer deaths, not vaccine deaths. And if a nuclear bomb could be blamed on Russia in any way, then Putin could be the scapegoat for global cancer deaths and the near-extermination of humanity.

Of course, the mRNA injections were necessary to set up the conditions for this mass die-off. Once in place, all the globalists needed was a new source of ionizing radiation to be released. And that’s fairly simple for the deep state, since Russian-made nuclear materials were smuggled out of Ukraine during the fall of the USSR in 1991, and western intelligence sources got their hands on Russian nuclear material during the chaos.

This means the globalist “deep state” has Russian nukes on hand and can set them off anywhere they want, then blame Russia for the heinous act. The obedient propaganda media of the west will gladly go along with the lie.

Similarly, Putin might actually be pushed into using his own nuclear weapons due to the extreme economic war actions that have been unleashed against Russia. We could then experience a global nuclear exchange involving several nuclear powers.

Either way, it’s clear that America and NATO are attempting to drive the world into a nuclear event of some kind, and as I’ve described in this story, I think we know the reason why. It’s the second part of the binary weapon for global depopulation.

The world is run by a suicide cult of demonic lunatics who seek the total destruction of the human race

I’ve stated this many times before, but only now are many people seeing how the dots connect. It’s now obvious that the attacks on humanity have been planned to take place in multiple vectors: Economic, biological, radiological, psychological, etc. When they are layered together on unprepared or weak-minded individuals, the result can be so devastating that their lives are quickly ended. This process is already under way and is being rapidly accelerated with the conflict in Europe. Bill Gates must be thrilled.

About 63% of the world has been injected with mRNA. Nearly 100% will be exposed to ionizing radiation as soon as the nuclear detonations (or dirty bombs) can be achieved by the globalists. 100% of the world population will face famine, starvation, fiat currency collapse and insane fuel prices due to the economic war that has recently been unleashed. And of course, nearly 100% of the population is subjected to the psychological terrorism of the lying corporate media and government propaganda.

Not surprisingly, very few individuals can withstand all of this with their minds and bodies intact. Count your blessings, because you are among these very few people.

Understand, though, that if the globalists achieve their desired escalation, many of the people you know will be dead within two years. They will die from “cancer,” from famine, suicide, lawless violence, immunological disorders, etc. Very few people who did not prepare will survive what is coming. For the most part, only the prepared will have a chance of making it through.

SARS–CoV–2 Spike Impairs DNA Damage Repair and Inhibits V(D)J Recombination In Vitro

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Antibodies and Reagents

2.2. Plasmids

2.3. Cells and Cell Culture

2.4. HR and NHEJ Reporter Assays

2.5. Cellular Fractionation and Immunoblotting

2.6. Comet Assay

2.7. Immunofluorescence

2.8. Analysis of V(D)J Recombination

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

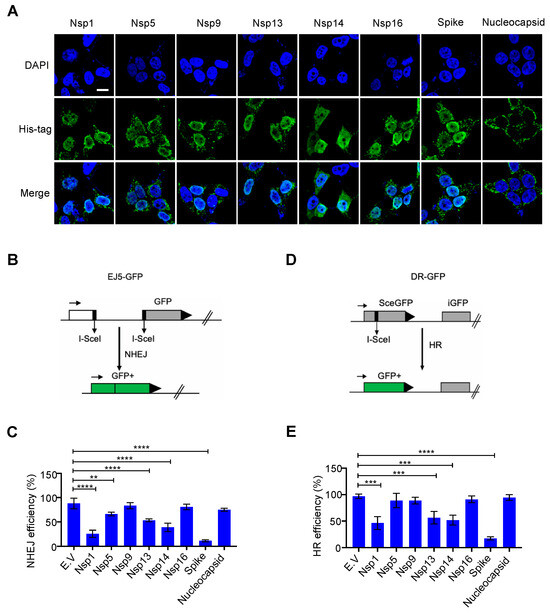

3.1. Effect of Nuclear–Localized SARS–CoV–2 Viral Proteins on DNA Damage Repair

3.2. SARS–CoV–2 Spike Protein Inhibits DNA Damage Repair

3.3. Spike Proteins Impede the Recruitment of DNA Damage Repair Checkpoint Proteins

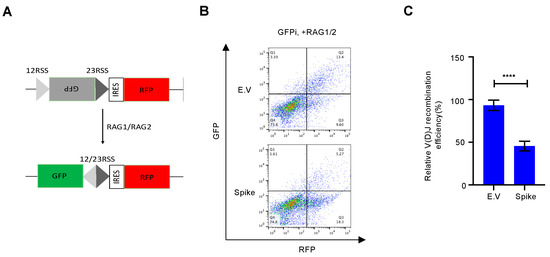

3.4. Spike Protein Impairs V(D)J Recombination In vitro

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- V’Kovski, P.; Kratzel, A.; Steiner, S.; Stalder, H.; Thiel, V. Coronavirus biology and replication: Implications for SARS-CoV-2. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2021, 19, 155–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suryawanshi, R.K.; Koganti, R.; Agelidis, A.; Patil, C.D.; Shukla, D. Dysregulation of Cell Signaling by SARS-CoV-2. Trends Microbiol. 2021, 29, 224–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, C.; Zhou, L.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, S.; Yang, S.; Tao, Y.; Xie, C.; Ma, K.; Shang, K.; Wang, W.; et al. Dysregulation of Immune Response in Patients With Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) in Wuhan, China. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 71, 762–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.; Nie, J.; Wang, H.; Zhao, Q.; Xiong, Y.; Deng, L.; Song, S.; Ma, Z.; Mo, P.; Zhang, Y. Characteristics of Peripheral Lymphocyte Subset Alteration in COVID-19 Pneumonia. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 221, 1762–1769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, G.; Nie, S.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, Z. Longitudinal Change of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 Antibodies in Patients with Coronavirus Disease 2019. J. Infect. Dis. 2020, 222, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Long, Q.X.; Liu, B.Z.; Deng, H.J.; Wu, G.C.; Deng, K.; Chen, Y.K.; Liao, P.; Qiu, J.F.; Lin, Y.; Cai, X.F.; et al. Antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 in patients with COVID-19. Nat. Med. 2020, 26, 845–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednarski, J.J.; Sleckman, B.P. Lymphocyte development: Integration of DNA damage response signaling. Adv. Immunol. 2012, 116, 175–204. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Malu, S.; Malshetty, V.; Francis, D.; Cortes, P. Role of non-homologous end joining in V(D)J recombination. Immunol. Res. 2012, 54, 233–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bednarski, J.J.; Sleckman, B.P. At the intersection of DNA damage and immune responses. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2019, 19, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gapud, E.J.; Sleckman, B.P. Unique and redundant functions of ATM and DNA-PKcs during V(D)J recombination. Cell. Cycle 2011, 10, 1928–1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Difilippantonio, S.; Gapud, E.; Wong, N.; Huang, C.Y.; Mahowald, G.; Chen, H.T.; Kruhlak, M.J.; Callen, E.; Livak, F.; Nussenzweig, M.C.; et al. 53BP1 facilitates long-range DNA end-joining during V(D)J recombination. Nature 2008, 456, 529–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwarz, K.B. Oxidative stress during viral infection: A review. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1996, 21, 641–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.H.; Huang, M.; Fang, S.G.; Liu, D.X. Coronavirus infection induces DNA replication stress partly through interaction of its nonstructural protein 13 with the p125 subunit of DNA polymerase delta. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 39546–39559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delgado-Roche, L.; Mesta, F. Oxidative Stress as Key Player in Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (SARS-CoV) Infection. Arch. Med. Res. 2020, 51, 384–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pierce, A.J.; Hu, P.; Han, M.; Ellis, N.; Jasin, M. Ku DNA end-binding protein modulates homologous repair of double-strand breaks in mammalian cells. Genes Dev. 2001, 15, 3237–3242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennardo, N.; Cheng, A.; Huang, N.; Stark, J.M. Alternative-NHEJ is a mechanistically distinct pathway of mammalian chromosome break repair. PLoS Genet. 2008, 4, e1000110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadofsky, M.J.; Hesse, J.E.; McBlane, J.F.; Gellert, M. Expression and V(D)J recombination activity of mutated RAG-1 proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993, 21, 5644–5650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trancoso, I.; Bonnet, M.; Gardner, R.; Carneiro, J.; Barreto, V.; Demengeot, J.; Sarmento, L. A Novel Quantitative Fluorescent Reporter Assay for RAG Targets and RAG Activity. Front. Immunol. 2013, 4, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Cruz-cosme, R.; Zhuang, M.-W.; Liu, D.; Liu, Y.; Teng, S.; Wang, P.-H.; Tang, Q. A systemic and molecular study of subcellular localization of SARS-CoV-2 proteins. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2020, 5, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shang, J.; Wan, Y.; Luo, C.; Ye, G.; Geng, Q.; Auerbach, A.; Li, F. Cell entry mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 11727–11734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, L.; He, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Liu, S.; Zheng, B.J.; Jiang, S. The spike protein of SARS-CoV—A target for vaccine and therapeutic development. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2009, 7, 226–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Yang, C.; Xu, X.F.; Xu, W.; Liu, S.W. Structural and functional properties of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein: Potential antivirus drug development for COVID-19. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2020, 41, 1141–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann, M.; Kleine-Weber, H.; Schroeder, S.; Kruger, N.; Herrler, T.; Erichsen, S.; Schiergens, T.S.; Herrler, G.; Wu, N.H.; Nitsche, A.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Cell Entry Depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and Is Blocked by a Clinically Proven Protease Inhibitor. Cell 2020, 181, 271–280.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, A.C.-Y.; Wang, G.; Reid, A.T.; Veerati, P.C.; Pathinayake, P.S.; Daly, K.; Mayall, J.R.; Hansbro, P.M.; Horvat, J.C.; Wang, F.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Spike protein promotes hyper-inflammatory response that can be ameliorated by Spike-antagonistic peptide and FDA-approved ER stress and MAP kinase inhibitors in vitro. bioRxiv 2020, 2020, 317818. [Google Scholar]

- Poland, G.A.; Ovsyannikova, I.G.; Kennedy, R.B. SARS-CoV-2 immunity: Review and applications to phase 3 vaccine candidates. Lancet 2020, 396, 1595–1606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davanzo, G.G.; Codo, A.C.; Brunetti, N.S.; Boldrini, V.; Knittel, T.L.; Monterio, L.B.; de Moraes, D.; Ferrari, A.J.R.; de Souza, G.F.; Muraro, S.P.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 Uses CD4 to Infect T Helper Lymphocytes. medRxiv 2020, 2020, 20200329. [Google Scholar]

- Borsa, M.; Mazet, J.M. Attacking the defence: SARS-CoV-2 can infect immune cells. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2020, 20, 592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barberis, E.; Vanella, V.V.; Falasca, M.; Caneapero, V.; Cappellano, G.; Raineri, D.; Ghirimoldi, M.; De Giorgis, V.; Puricelli, C.; Vaschetto, R.; et al. Circulating Exosomes Are Strongly Involved in SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2021, 8, 632290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sur, S.; Khatun, M.; Steele, R.; Isbell, T.S.; Ray, R.; Ray, R.B. Exosomes from COVID-19 patients carry tenascin-C and fibrinogen-β in triggering inflammatory signals in distant organ cells. bioRxiv 2021, 2021, 430369. [Google Scholar]

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

|

Leave a Reply